The Optimist's Guide to the Caltrain

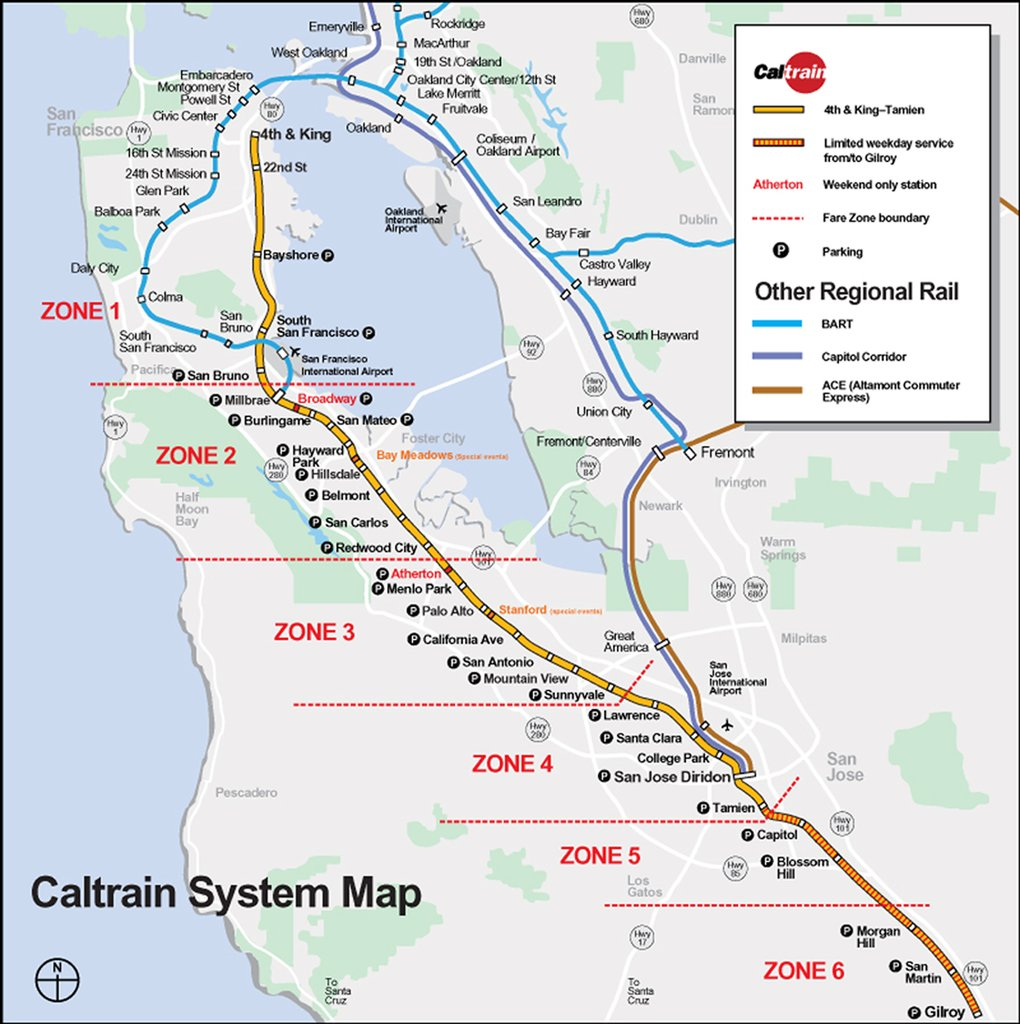

As a millennial, I am totally still a young person1 and therefore familiar with the Glow-Up: a personal transformation so complete that the “after” and “before” pictures look like totally different people. It will come as no surprise to folks that know me that I love watching the same thing happen to transit systems, and there’s a great example taking shape right in my backyard. If you’re a Bay Area commuter, or just a person who read the title of this post, may have already guessed that I’m talking about Caltrain, the commuter rail line that carries me and about 60,000 other daily passengers between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. As the only extant rail link between these two great symbols of man’s hubris, the system is an indispensable alternative to the 101 freeway, which during the morning is a soup of Google shuttle buses and too-clever-by-half Teslas algorithmically jockeying for open lanes. It’s also long lived in the shadow of BART, our regional rapid transit network. Caltrain goes where BART doesn’t, and the great lament of Bay Area transit nerdery is that BART doesn’t ring the bay, and instead of its fast, frequent, electric trains, Silicon Valley is stuck with slow, sparse, diesel Caltrain service.

While complaining about Caltrain is the national pastime of the country Silicon Valley will be when California accidentally votes to secede and split itself into five states in 2020, the system is in some ways a victim of its own success. Ridership has more than doubled in the past ten years, trains are packed to the gills during peak commute times, and between the diesel trains, numerous grade crossings, and sparse off-peak service, Caltrain’s weary, twentieth-century bones are starting to show. Luckily, after decades of stops and starts, an Alpha-Bits box of ballot measures, and a harrowing run-in with transportation secretary Elaine Chao, Caltrain is about to receive a slate of major upgrades, starting with the Caltrain Modernization (“CalMod”) project to run quieter, faster, greener electric trains. Unsurpringly, the construction work required is going to make service worse in the short term, starting with temporary cessation of weekend service within San Francisco this October.

What do we get for these disruptions? My hope is that we’re taking the first steps towards Caltrain matching and maybe even exceeding BART in frequency, speed, and comfort (okay, that last one shouldn’t be that hard). And since one rationale for improving Caltrain is that its tracks will eventually, maybe, inshallah, be shared by the beleaguered California High Speed Rail project – henceforth CAHSR because my fingers hurt – we have a chance to lay the groundwork for a “blended” rail system where local and express Caltrain service happily coexists with high speed rail, sharing tracks, platforms, and maybe even a unified fare system. In this post I’d like to peel back the before-and-after pictures to better understand Caltrain’s glow-up as a series of techical, incremental improvements whose individual effects we can understand, evaluate, and advocate for. While electrification is a prerequisite for this optimistic future, I hope that your takeaway from reading this is that electrifcation is just the beginning of Caltrain’s transformation from ugly duckling to utilitarian but highly effective adult duck (metaphors were never my strong suit). Adding up all the changes slated for the next decade or so, we have a lot to look forward to – and BART had better watch its back.

Staying current with electrification

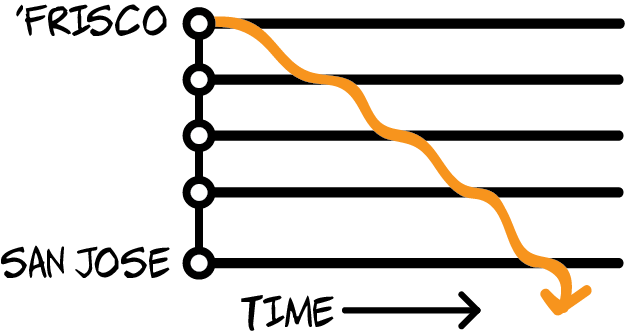

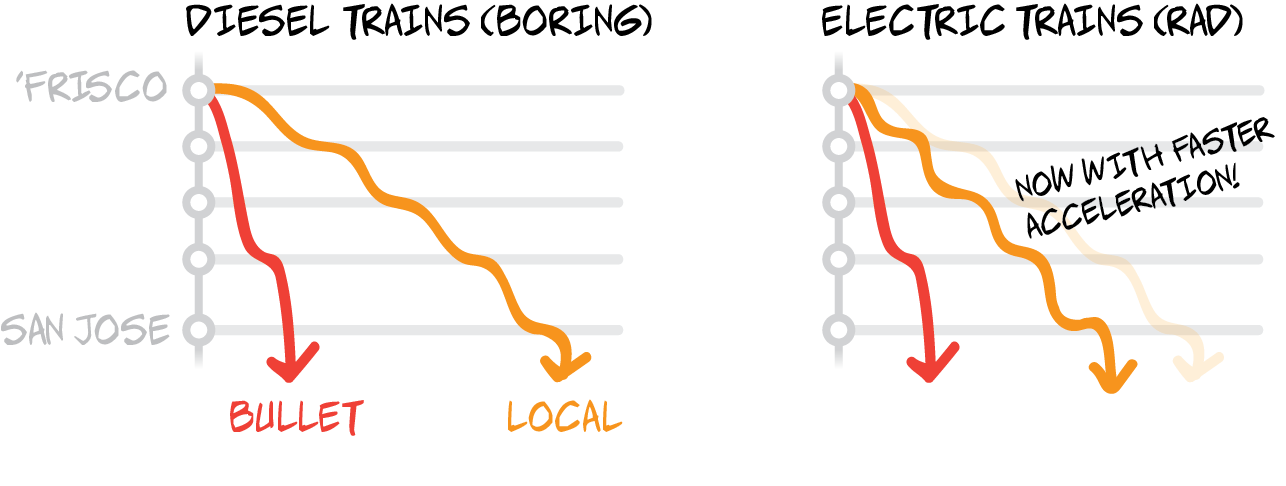

If you’re looking to blow an entire afternoon, you should check out the whole YouTube genre of electric car owners (including Electric Car Owner Number One) demonstrating how their cars’ induction motors blow the zero-to-sixty of traditional internal combustion engines out of the water. This neat and probably dangerous quirk of EVs turns out to be the primary benefit of electric trains over their diesel-guzzling brethren. Faster acceleration means it’s possible for trains to spend more time at their maximum allowed speed, which is particularly important when you make as many stops – 21! – as your local Caltrain does between San Francisco and San Jose. While it’s possible that electricty was known to the ancient Persians, American commuter railways have with relatively few exceptions failed to catch on to this mysterious phenomenon as a means of train propulsion. Railways in other parts of the world use trains called Electric Multiple Unit (EMUs, and not this kind), where each car draws power from an overhead wire and carries its own motors. Since each car propels itself, you can string them together with reckless abandon without really affecting their ability to accelerate quicky.

For a few reasons, these are less common in the United States. First and foremost, we don’t deserve nice things. More practically, commuter systems such as Caltrain often share track with much heavier freight trains. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has more stringent standards for train “crashworthiness” than in other countries — and most EMUs don’t meet these standards, though they operate just fine in similar conditions in Europe. By committing to further safety improvements, loudly reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and promising to stop affectionately referring to Colin Kaepernick as “Kap”, Caltrain was able to procure an waiver from the federal government that permits them to buy and run European EMUs. We now have 96 Stadler “KISS” EMUs en route, and we’ll likely be purchasing another batch of 96 in the next few years. Don’t start refreshing the delivery tracker just yet, though – the trains won’t get here until 2020 and won’t be running until late 2021 at the earliest.

A notable drawback: electric trains require more onboard space for flux capacitors or whatever, and don’t have as much seating capacity as any of the existing Caltrain cars; they’ll average 681 seats per 6-car train instead of today’s 741. To make up for this, Caltrain can and will run more peak-hour trains after the EMU procurement – according to its projected timetables, anyway – and in fact most express service will continue to use the existing diesel trains until the second batch of EMUs comes in. All told, Caltrain projects a peak capacity increase of 10%, and this number jumps to 31% counting standing-room-only2. We could further improve this by lengthening trains (as well as platforms) to eight cars or so. Not bad, but this is really only the beginning.

Keeping track of trains with positive train control

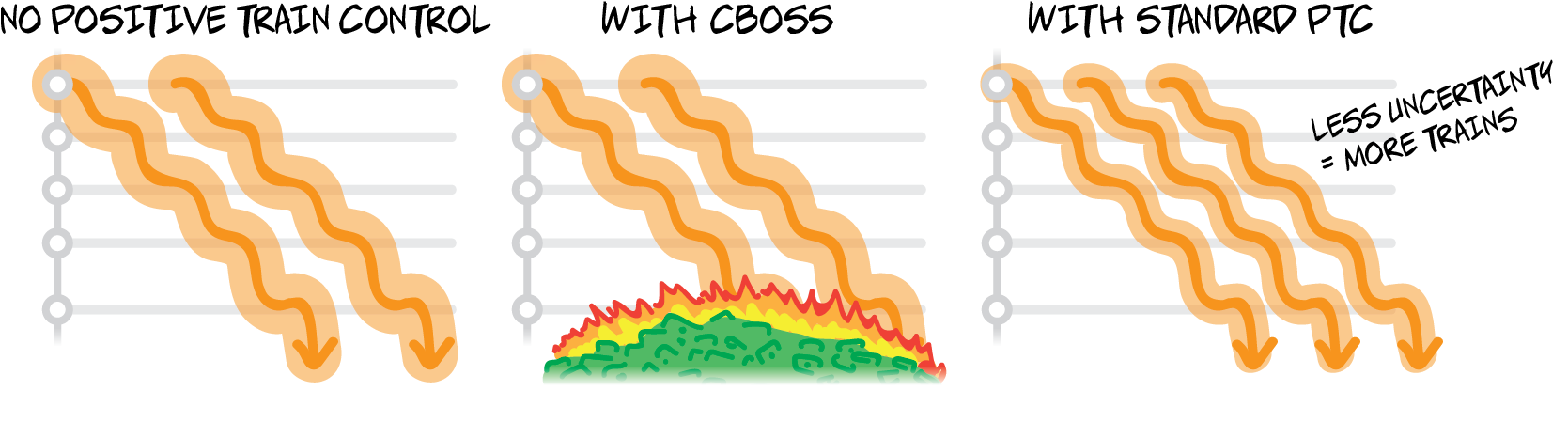

Remember that part about not crashing into freight trains? Just like cars, trains are subject to speed limits and traffic signals, but since an accident in 2008, our friends at the FRA have gotten serious about enforcing these rules with computers instead of just two dudes pointing at things. This is called Positive Train Control, or just PTC – a system that accounts for things like track curvature, road crossings, and other trains in order to calculate and enforce a speed limit for each train in real time. While PTC isn’t a new thing and there are plenty of existing implementations, Caltrain initially took it upon themselves to design an entirely new system called CBOSS. Though widely considered a risky move, the $261 million project was completed on time and under budget.

Haha, no, I was just joking. After about six years of missed deadlines and slipping budgets, the agency has basically thrown its hands in the air and decided to pay for implementation of a standard PTC system called I-ETMS, in the hopes of meeting a December 2018 deadline for demonstating the technology in operation. Not all of the money spent on CBOSS was wasted, since a lot of the electronics can be reused, but Caltrain expert Clem Tillier ran the numbers3 and determined that the agency lit about $150 million in tax dollars on fire trying and failing to get CBOSS up to snuff. Okay, bad, but I still haven’t answered your question: what is positive train control, and what is this cool quarter billion dollars going to get us?

You can’t point to a single object and say “that’s PTC”, which makes it an inevitable budget black hole – when nothing’s PTC, everything is. I’ll try my best though: it’s a series of electronic sensors, both trackside and on trains, as well as complicated monitoring and dispatch software, and a series of protocols for using all of this technology correctly. Put together, it basically gives us higher confidence in where trains are and how fast they’re going, because it imposes a strict speed limit with computers – but encourages operators to hug that limit, ultimately improving performance. Electrification and PTC are the two major line items in the “CalMod” project that’s currently underway, and they’ll go a long way in helping Caltrain keep up with growing demand. For further improvements, we’ll need to dive into project that are murky, speculative, and (gasp) unfunded.

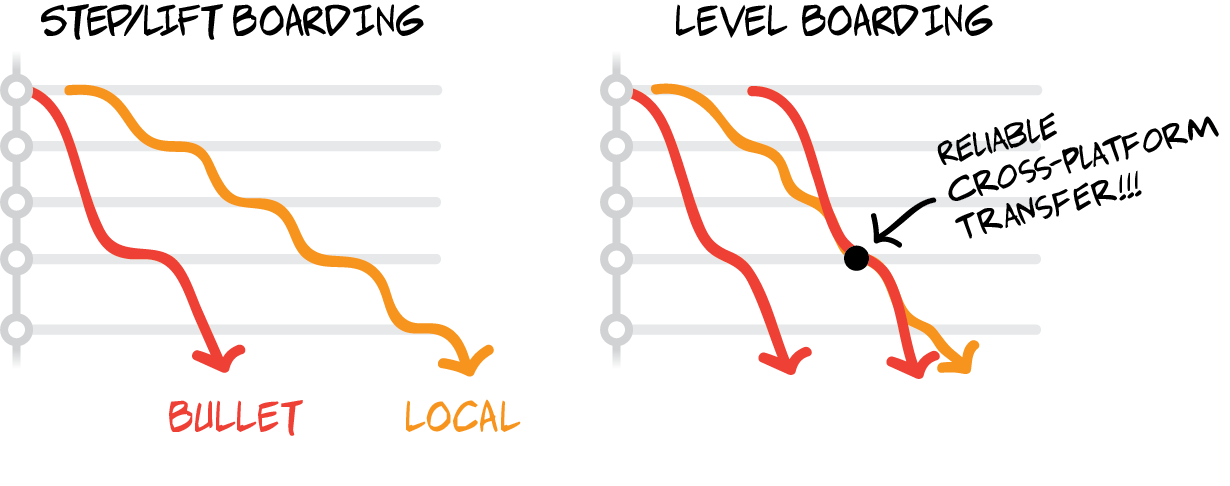

Minding the gap with level boarding

Can we make the train faster when it’s not moving? This might sound like a zen koan, but consider this: Caltrain got some consultants to go out and watch their trains pull into stations for a few weeks, and these poor souls reported a systemwide median dwell time (time stopped at a station) of 48 seconds. That adds up to more than 15 minutes of standstill on a local train from San Francisco to San Jose. Not only do we need to account for dwell time when spacing trains out, but it also depends on passenger volume, so we can’t really know in advance how much any stop is going to require. Sure, Millbrae in the mornings is always going to be busy thanks to its BART connection, and no one will ever get on or off at Hillsdale because it’s a cursèd place, but there’s a certain amount of padding built in to account for extremely heavy passenger loads, or passengers who need assistance boarding with a wheelchair. Our tool for shortening dwell times is level boarding: train doors and platforms built to the exact same height so that you can board and alight without encountering a step, whether you walk, wheel, slither, or wumbo on board. This makes dwell times shorter and more predictable – in a very real sense, it makes the trains faster at zero miles per hour.

Since some of Caltrain’s platforms will be shared with CAHSR, implementing level boarding requires some forethought. CAHSR trains will have level boarding at 50” above the rail, so Caltrain needs doors at that height, or boarding the train will be like climbing into a sewer grate. Right now, though, Caltrain platforms are at 8” – and a staircase between those two heights would be prohibitively steep. The upgrade of both trains and platforms will be a long, iterative process – how will we manage in these years of transition? A firelit boardroom full of old men in suits gnaw at their cigars, turning the question over in their mind. Then: “what if we had two sets of doors on the train?”, the Caltrain intern volunteers shakily from across the room. By Jove, the whippersnapper’s done it!

Sure enough, the Stadler EMUs are designed with two sets of doors, at 25” and 50”, to faciliate low-step boarding today while also preparing for a future of compatibility with HSR. While its vehicles are at least future-proofed, Caltrain has been having trouble ironing out the details of which stations are going to get level boarding at what height, when. Because of CAHSR, we’re going to have to rebuild the platforms at major stations at least once, raising them to 50” and lengthening them to support longer high-speed trains. It would be nice if this could happen exactly once in the next few decades, but given that high speed rail may not make it to the Bay until sometime beginning with “stardate”, we should be prepared to press on with or without it.

There is some latent danger here of bad operations permanently hamstringing a very expensive concrete investment. One potential outcome is that Caltrain builds 25” platforms without a plan to eventually convert them to 50”. In this case, we could end up segregating CAHSR and Caltrain trains onto different sets of platforms, forcing us to overbuild shared stations while also preventing us from using them to their full capacity. Actually understanding Caltrain’s perspective on this issue requires advanced spelunking their meeting notes and planning documents, so I rely (again) on Clem Tillier to keep me up to date on how they’re doing. Getting level boarding right is priority #1 for correctly “blending” Caltrain and CAHSR operations, and applying gentle pressure on Caltrain to get their shit together and finalize a plan for when and how platforms will be raised is something we can all do next time they walk around the trains handing out survey cards.

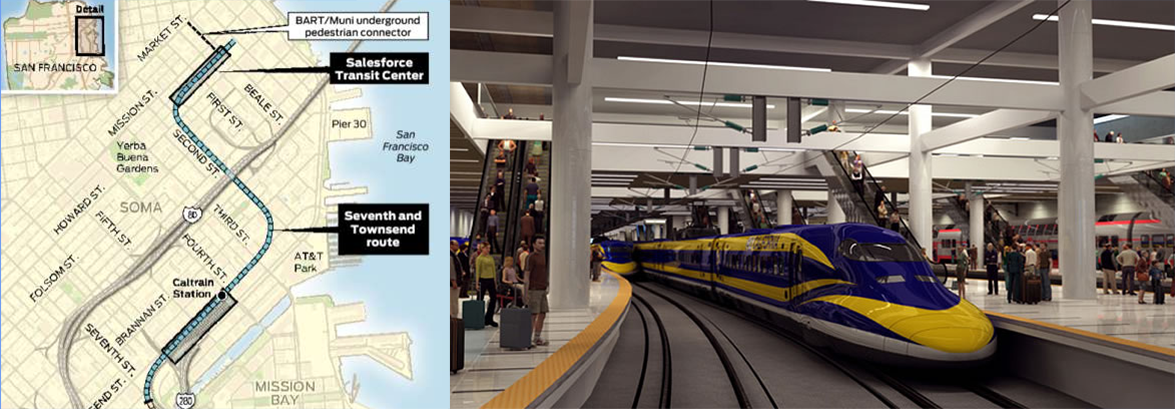

To Transbay and beyond

Earlier in 2018, the Transbay Transit Center4 in downtown San Francisco opened to great fanfare…then immediately closed temporarily to address structural issues. While it currently the world’s glitziest bus terminal, below the surface lies what engineers have creatively termed a “train box” – a blocks-long cavern that in 2029 or so will hopefully be the northern terminus of Caltrain and CAHSR trains. This “Grand Central of the West”, as some consultant decided to call it, represents the literal and metaphorical final stop (I lied earlier, metaphors rule) on Caltrain’s journey from rickety commuter train to star of the region’s rail network. The Downtown Extension (DTX) project to connect Caltrain to the city’s central business district is a big deal, not just because of the amount of jobs there – they outnumber those near every other Caltrain station combined – but because of connectivity to the larger Bay Area rail network. The Caltrain-BART connection at Millbrae is bad, and the region’s rail network will benefit enormously from having another one downtown.

For all of my excitement, planning for DTX is going about as well as you’d expect. The terminal’s planned six platforms and the long, slow approach towards them will constrain the system’s capacity in a way that will probably force us to continue routing some trains toward the current surface terminal at 4th and King. The project’s $6 billion budget is comically bloated; transit guru Alon Levy writes that cost per rider is orders of magnitude higher than other tunneling projects in Europe, and suggests common-sense improvements: dig shallower tunnels, share platforms between Caltrain and CAHSR, don’t lay more track than you have to. I’ve written before about the difficulties of parking trains downtown; in the long term, the Transbay Center probably makes the most sense as just another stop before Caltrain’s ride through a proposed second Transbay tube. One could imagine Caltrain sprouting branches through the tube (and also across the Dumbarton bridge) into the East Bay, ultimately forming a regional rail network complementary to BART, but tightly integrated with its schedules and fare structure. One could even imagine a future where Caltrain, now providing the greater Bay Area with true rapid transit, could adopt a name…perhaps an acronym of some kind…that somehow encapsulates this role. Hard to imagine what it might be now, but I’m sure we’ll think of something.

A real chance for something great

The peninsula that Caltrain serves is one of the wealthiest and most economically productive places in the world. Yet its freeways, cul-de-sacs, and sprawling suburban tech campuses both inform and exemplify the self-reliant, insular ethos of Silicon Valley, which is increasingly exported to the rest of the world by the likes of Facebook and Uber. Living here day to day, I am often struck by how unsustainable it all seems – the fantastic opulence and technical expertise siloed up in towers of sheer indifference towards solving the basic problems of housing and transportation in the communities used as a substrate. Anything that can make this place feel more connected, accessible, and equitable increasingly seems like an investment in not just the Bay Area, but everywhere that lies in the long shadows of Apple and Google’s walled gardens.

Jeez, I need another coffee – we were talking about trains, right? While improving Caltrain won’t exactly fix Silicon Valley, it’s very heartening to see that the agency sees BART-style “show up and go” rapid transit service as the endgame of its planned improvements. To quote one of their truly innumerable planning documents:

[Our study] suggests that providing BART-like frequencies on the Caltrain Corridor has the potential to yield BART-like ridership. Today, Caltrain serves approximately 1,300 daily passengers per mile between San Francisco and Tamien Stations, while BART serves approximately 5,200 passengers per mile along its Richmond-Daly City and Fremont-Daly City trunk lines. The sensitivity test suggests Caltrain has a long term (2040) unconstrained demand of about 4,600 passengers per mile. – Caltrain Business Plan, September 2018 update

In human terms, this means that Caltrain understands that if they run more trains, enough people will ride them to make the investment worth it. This is why I’m optimistic about Caltrain’s future. Electrification, PTC, all this technical stuff you’ve been kind enough to humor me about – they’re not important because Train Stuff is Good5, but because they’re stepping stones on the way to true rapid transit that could connect and transform communities up and down the Peninsula. That Caltrain itself understands this makes it worth obsessing about details like door positioning and seat count, because there’s a real chance for us to get this right in a big way. So on Monday morning when I stuff myself onto a southbound Caltrain, the smile on my face will have nothing to do with the train I’m on (believe me) – I’ll be daydreaming about the one that’ll take its place.

- “Level platforms are…bae? Positive train control is…lit??”, I scribble onto a page of my insufferable Moleskine notebook, before crumpling it into a ball and whipping it across Sightglass Coffee. [return]

- Counting standees seems quite fair given that many BART commuters have long-haul standing commutes, but standing on Caltrain is an unenviable position to be in. [return]

- This post is in many ways simply the Cliff’s Notes of this other guy’s blog, and if you found this at all interesting you should check it out for an endless treasure trove of actual expert analysis of Caltrain’s plans for its future. [return]

- We do not speak its true name [return]

- For the record, though, train stuff is good. [return]