The carbon calculus of high-speed rail

For a few weeks each year, often coinciding with the latest climate accords, emergency summit, or wildfire, the United States collectively kicks around the idea of saving the planet. This year, I feel slightly more optimistic that all the talk will eventually lead somewhere, thanks to actually-good congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a bunch of ne’er-do-wells kicking around in Dianne Feinstein’s office, and their renewed calls for a Green New Deal bill to push the nation towards carbon-neutrality. As it stands, the Green New Deal is more of an idea than a concrete proposal. While it has a long way to go before it can be massaged by Congress into a set of tax breaks for mildly repentant oil companies and eventually passed into law, it’s refreshing to see folks in government proposing solutions that at least acknowledge the scale of the problem.

You can read the text of the resolution put before Congress, “Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal”. Of particular interest to me is the call for investment in high-speed rail (HSR) in the Transportation section. Occasionally, and to my great chagrin, I’m introduced as “the trains guy” at parties, so I’m naturally excited to see this. Instead of a tiny metal box trapped between other metal boxes on the freeway, or a flying metal tube full of pretzels doing to the atmosphere what hookah does to your lungs, we could be travelling in style in an extremely long metal tube featuring ample legroom and a full-fledged bar, gliding smoothly on electric power from city center to city center. HSR really does blow cars and airplanes out of the water on emissions and comfort…if we ever manage to build any.

The only high-speed rail project currently underway in the US is California High-Speed Rail (CAHSR), and over the past 10-20 years its budget has steadily climbed to $77 billion, or almost two years of war in Afghanistan. The governor has recently been quite candid in saying that the state doesn’t know where the money will come from to complete the LA to San Francisco rail line. There’s no doubt that these costs are higher than they need to be, partially because of the unnecessarily rigorous speed mandate imposed on the project. There’s also no doubt the United States can regularly absorb this kind of expense; we are a nation that inevitably finds the money for the things we prioritize on the national, state, and local level, while comically turning our empty pockets out for the things we don’t. HSR is financially within reach of the United States, and there are great reasons to build it that have nothing to do with the environment. Here, though, I’m interested in understanding its cost-effectiveness as a tool to fight climate change to determine whether it should have a place in a focused, well-crafted Green New Deal.

The part with spreadsheets (wait, don’t go!)

To quantify the environmental benefits of CAHSR, we’ll try to measure how much CO2 we would otherwise emit without it; this figure depends on the number of riders an HSR system has, and which more emissions-heavy mode of transport they would have used in its absence. For “Phase 1” of the system, which will run from LA to San Francisco, the state’s estimate is around 29 million riders per year. Some people at Berkeley think that’s a little high, but for argument’s sake let’s run with it as a squishy upper bound. After hours of digging around in document archives, I found some spreadsheets that list ridership projections between each area of California served by CAHSR. Here I’ve adapted spreadsheet for Phase 1, changed the location names to be human-readable, and calculated the estimated CO2 savings from high-speed rail, shown below:

It’s easy to get lost in the sauce of these numbers, so let’s do a very simple baseline calculation to see what kind of order of magnitude we expect. The distance from Los Angeles to San Francisco is about 380 miles1. A single mile of driving in an average car emits 0.36kg of CO2. Multiply 380 mi * 0.36 (kg / mi) * 29 million / (1000 kg / 1 metric ton) and you get about 4 million tons of CO2 diverted per year by HSR. So we expect something in that order of magnitude, though probably lower once we account for the precise distances involved and the average number of passengers (1.7) in each car. The spreadsheet spits out 1.6 million tons of CO2 per year diverted from high-speed rail2, and who am I to question it?

This is a good start. However, operating an electric train is not carbon-free if we’re burning carbon to produce the electricity, so we need to take those emissions into account as well. We can get a vague sense of the CO2 burden of CAHSR operations by piecing together the following enigmatic internet clues:

- HSR trains in China consume only (?) 3.8 kilowatt-hours per 100 passengers per km

- I was pleasantly surprised to learn that California only gets 38% of its electricity by burning carbon-based fuel. Let’s optimistically say that this number is 25% in about 10-15 years when Phase 1 is finally complete.

- The bulk of that fuel is natural gas. Producing one million (rubs temples) British thermal units of energy from natural gas emits about 53kg of CO2.

This is giving me terrible flashbacks to AP chemistry and dimensional analysis, but luckily Wolfram Alpha has only gotten better since those days, and it tells me that all of this crunches out to about 30,000 tons of CO2 per year to run all of these trains, which is less than 2% of the total CO2 diversion we calculated above. Not bad at all!

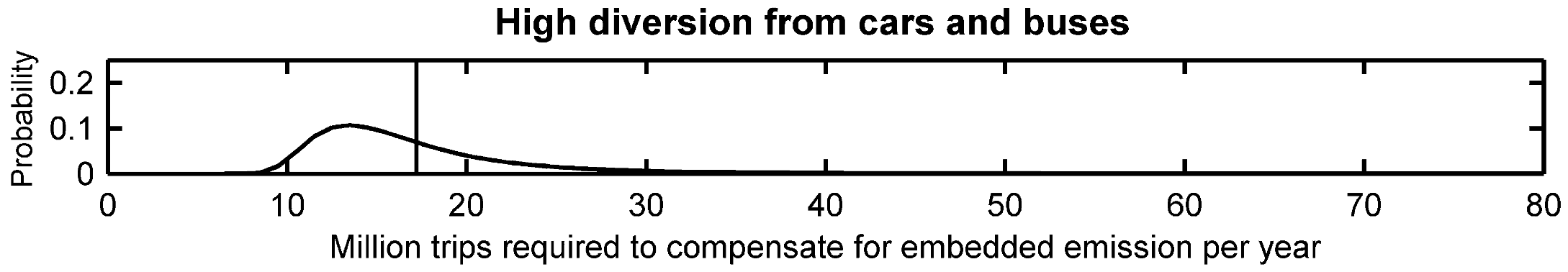

Unfortunately, we have yet to account for the emissions cost of actually building the rail line. Willing 380 miles of train into existence involves big concrete viaducts, literally blowing up mountains, and all sorts of other carbon-intensive work. It’s far beyond my ability to do this kind of analysis, but luckily it’s someone’s job – specifically Jonas Westin and Per Kågeson, who produced a paper that modeled CAHSR fairly closely in terms of length and construction criteria. A CityLab article about their findings is available here, but I have jumped the paywall for you and retrieved this somewhat grim figure:

What this graph tells us is that a high-speed rail system like CAHSR needs to serve around 15 million yearly passengers, and probably more, to even offset the carbon cost of its construction3. That’s about half of the 29 million passenger estimate! The error bars on all of these numbers are pretty big – and I’m fortunate that I’m not being paid to write this or I’d probably have to tell you how big – so let’s just keep it simple. The ridership model predicts about 1.6 million tons of CO2 diversion. We know the cost of building and running HSR will eat about half of that. I’m pretty comfortable saying that the net carbon savings offered by CAHSR is 500,000 to 1 million tons of CO2 per year4.

The part where we add context

500,000 tons is an incomprehensibly large number. For my part, I’ve been going to the gym for a while and I’m almost certain I wouldn’t be able to bench that. Just to put that in context, though – time to take a big sip of coffee and look up the United States’ total CO2 emissions from transportation.

1.85 billion tons?

That’s…well, it’s a bigger number, and it makes the CO2 that CAHSR saved us look like small potatoes once you realize it clocks in at about 0.025-0.05% of the nation’s total transport-related emissions. For a single infrastructure project, maybe that’s not so bad in country of 300-something million people, some going out of their way to pollute as much as possible. But HSR isn’t being built in a vacuum5. Not only will its relative carbon benefits decline as electric cars rise to prominence, but there is a whole world of more cost-effective transportation investments we can make starting today. Once we investigate those, the argument for including high-speed rail in a green infrastructure bill starts to fall apart.

Let’s take a very generous estimate for CAHSR’s annual carbon savings to be a million metric tons, at the cost of $77 billion to construct. That’s 0.1% of the total emissions of all US passenger vehicles. To beat CAHSR on carbon savings, we have to negate the emissions 0.1% of United States drivers, or roughly 215,000 people. With a budget of $340,000 per driver, this is laughably easy, and I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader to decide whether we should buy them all ten electric cars, or blanket a lucky medium-sized metropolitan area with a gratuitous network of subway lines.

Fun as it is, this exercise misses the more alarming point that the price point of CAHSR implies a $77 trillion budget to wipe out the emissions of just passenger vehicles, which themselves account for just 17% of the United States’ total emissions. The prospect of passing legislation that makes us carbon-neutral is tantalizing, but there will be countless missteps and setbacks along the way. For political and practical reasons and we can’t afford to put anything but the most cost-effective eggs into our emissions reduction basket.

Trains are nuclear…6

Once upon a time, the future of the United States was nuclear. At the height of the Atomic Age, futurists pointed to early successes in fission power and claimed that, one day, nuclear energy would be “too cheap to meter”. It didn’t pan out like that, and today nuclear accounts for about 10% of our energy mix, a number that will continue to fall. Part of the reason is the danger inherent in nuclear power; though often vastly overstated, the worst-case failure mode for a nuclear power plant is considerably worse than that of other energy sources7. But it was ultimately construction costs, not NIMBYism, that relegated fission power to its current fate.

In the time it has taken a single nuclear reactor to enter service since the year 2000, both natural gas (ugh) and renewables like wind and solar (yee) have leapfrogged nuclear’s fraction of the United States’ energy mix. These options require much less up-front investment to get working; if you’re the president in 1979, you can throw some solar panels on the roof and start powering your, uh, 8-track player, though some asshole may take them down later. If you want natural gas, you can just pick a small town with poor legal counsel, start fracking, and hope you don’t cause any earthquakes. By contrast, nuclear power requires a huge, risky upfront investment and sometimes decades of construction before the first watt is generated, which is why hundreds of planned and partially-constructed reactors in the US were ultimately cancelled. You can probably see where I’m going with this.

High-speed rail is the nuclear power of the transit world. Both are ambitious, utopian, and a rich source of envy for Americans willing to look beyond our borders for more sustainable models of living. In some ways they’re head-slappingly obvious remedies to some of our biggest challenges. But they also require the same billions of dollars, years of time, and Moses-like ability to channel the tides of public opinion to shepherd a single project from paper napkin to ribbon-cutting. Like nuclear power, the appetite for high-speed rail has waxed and waned over the decades, but it’s never quite had its day. Climate advocates know that in shifting political sands and with the clock running down to avert greater disaster, we don’t have time to push nuclear, as good as it looks on paper, and I think the same logic needs to be applied to high-speed rail.

…And buses are solar

This certainly doesn’t mean that transporation investments don’t have a place in the Green New Deal, but we should aim for cost effectiveness at an order of magnitude higher than CAHSR. With $34,000 per displaced car commuter as a benchmark – that’s CAHSR’s figure divided by ten – we have plenty of options. Cost-effective, well-built subway projects fall into this range, though it should be noted that these are usually built in cities where they’re likelier to displace bus rides than car trips. And it can’t be ignored that electric cars can be purchased in this price range, though I hesitate to emphasize them since they’ll still burn through much more energy than any transit alternative, and will continue to enable sprawly land use patterns that are themselves inherently carbon-intensive. The most effective transit projects, those that deserve top billing in a Green New Deal, are those with the same qualities as solar panels: cheap, tactical, commodity solutions that can be deployed in weeks rather than years and are easy to scale.

Everyone playing the Yelling At Trains drinking game has to take a shot because I am, of course, talking about buses, those lomg, misunderstood chariots of the red lanes. Urban busway projects could displace drivers at costs closer to $10,000-15,000 per new rider. The most cost-effective investments will be the bravest: those that assert primacy of transit in our cities, even when it means closing some streets entirely to cars. Toronto did this last year by making King Street exclusive to streetcars, and the results were astounding. Not only did the streetcar line become much more reliable, its ridership increased by 12,000 passengers per day at a total cost of just $1.5 million. That’s $125 per new rider, a figure so breathtaking I had to punch it into the calculator a few times before I believed what I was seeing. If transportation planners can dig deep, be bold, and focus on the kind of investment the climate needs right now, they’ll have the best chance at shaping a popular, effective, and sustainable Green New Deal – and hopefully have some cash left over to build high-speed rail on its own merits.

- Coincidentally it’s the same in the opposite direction as well. [return]

- This model doesn’t account for the 2% of trips including an “OTHER” destination that I wasn’t really able to guess a travel distance for, so the number might be, roughly speaking, about 2% higher. It also doesn’t account for the “last leg” of trips involving Sacramento and San Diego, which in this model don’t have their own stations yet, so we lose some savings back to car (or ideally, bus) travel to reach these final destinations until the HSR segments connecting these cities directly come online. [return]

- Over the next 50 years. [return]

- I’m astounded and delighted to report that my bullshitting up to this point tracks pretty well with the number suggested for a similar system in Sweden. [return]

- Well, it might be, if the Hyperloop ever amounts to anything. [return]

- Just to be honest up front, this isn’t going to be about Snowpiercer. [return]

- Though it’s a strong field. [return]