Boston should buy transit in bulk

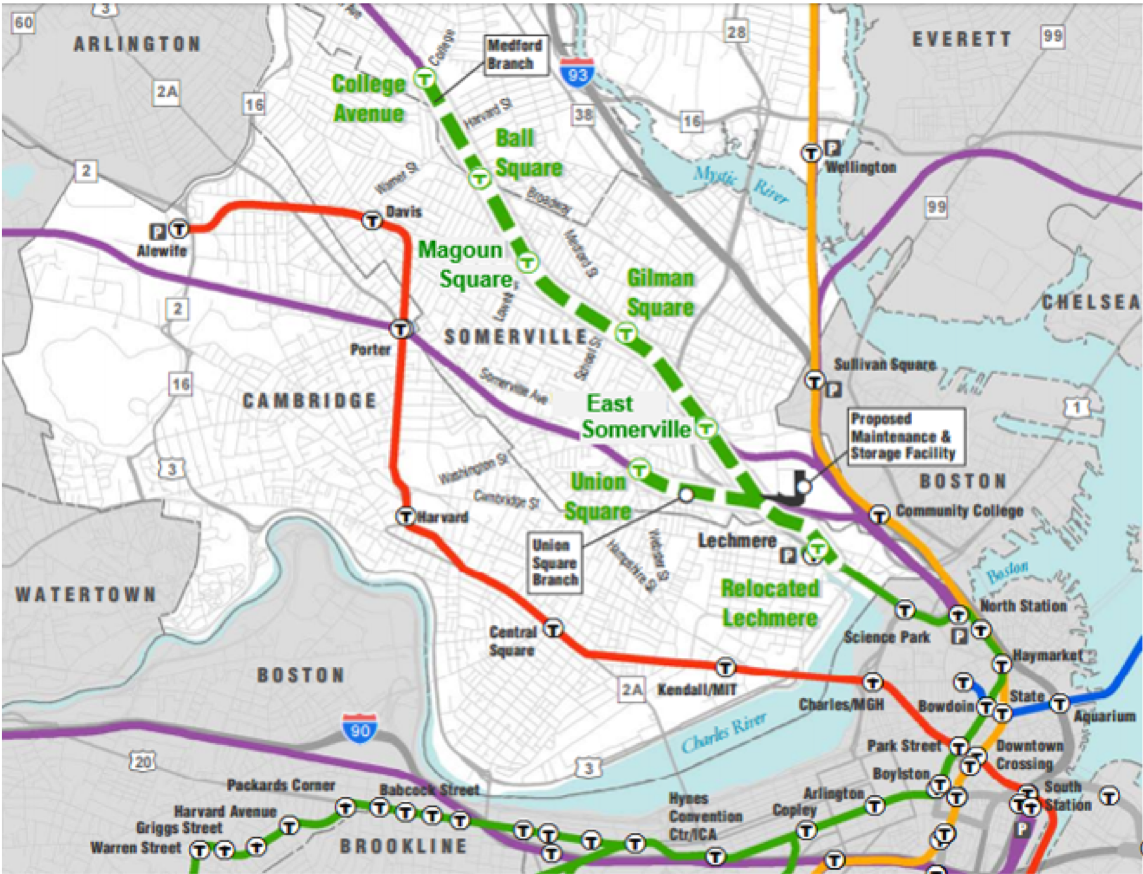

I don’t want to be the one to jinx it, but the MBTA – “the T” to its college drinking buddies – appears to really be building the Green Line Extension (GLX) to Somerville, finally fulfilling a prophecy inscribed on a mysterious ivory dagger excavated during the Big Dig. This is the agency’s first urban rail expansion since the mid 1980s when the Red Line was extended as far northwest as standard-issue Catholic racism would permit, and it’s particularly exciting because it came very close to not happening at all. In 2015, the MBTA announced that the cost the project was spiraling out of control. After two decades on the drawing board, its budget had gradually ticked up to $2.2 billion. Now, an increase of another billion dollars brought the total above $3 billion for less than five miles of light rail – in an existing trench for commuter trains! While the budget’s line items certainly added up to the newly quoted figure, taken as a whole the project had exited even the exosphere of cost control, and nobody at the MBTA really knew why. In late 2015, the agency cancelled the remaining contracts and put the extension on hold.

The GLX fiasco is far from an isolated incident. Recent additions to older subway systems – New York’s Second Avenue Subway and San Francisco’s Central Subway, to name a few – have consistently suffered from years of delays and billions of dollars in cost overruns. There are some well-understood reasons that transit construction costs so much: we pay high wages (rightfully so, for dangerous work) but overstaff construction sites. We suffer from a nasty case of “Not Invented Here” syndrome that prevents us from using modern design practices from around the world. We have many layers of governance, and sprawling metropolitan areas, that require planners to interact with many cities as well as state and county officials. Thinkpiecery about American transit construction accurately explains these factors, and laments that we rarely build new transit because it’s so expensive. But perhaps it omits the other half of a vicious feedback loop: transit is so expensive because we rarely build it.

In many cities rapid transit expansions have nearly become a once-in-a-generation affair: each one is a tangle of uncertainty for transit agencies inexperienced in overseeing construction projects – and a meal ticket for contractors preying on their hapless counterparts in the public sector. High costs and slipping timelines are not just devastating to the projects that they directly affect; they kneecap regional ambitions, normalize our low expectations, and most importantly, push back the planning of other projects by years or decades. This ensures that transit agencies pay the same startup cost over and over, and convince themslves that miscommunication, graft, and overdesign are fundamental to transit expansion.

I suspect that we can do a lot better; it’s just that we’ve forgotten how. I’d like to discuss how “buying transit in bulk” could turn our vicious cycles into virtuous ones; by this I mean planning breathtaking, decades-long system expansion now and asking voters directly to chip in today in exchange for a radically improved future for their city in a few decades. This sounds like a hard sell, but over the past few years it’s been done successfully by two major cities trying to bootstrap their transit networks rather late in the game. In 2016 Los Angeles’s Measure M and Seattle’s Sound Transit 3 ballot initiatives raised $120 billion and $54 billion, respectively, from voters to build out their rail and bus systems and pedestrianize their streets1.

I am here to timidly suggest that this might work at least as well in older American cities with transit networks no longer adequate to address their growing crises of congestion, emissions, and housing affordability. While Philidelphia and San Francisco also come to mind, I’ll continue to pick on Boston throughout this post. The time is not quite ripe for our beloved MBTA to go to Costco for a whole pallet of new transit, but after clearing a backlog of much-needed maintenance projects, I think we should be prepared to advocate for this by the early 2020s. That gives us a little breathing room – you all can take a quick stretch break and grab some hot chocolate if you like, and come back when you’re ready for a ~cautionary tale~.

In Which Construction In Boston Goes Over Budget

The Green Line Extension’s 2015 brush with cancellation was a moment of reckoning for the MBTA. GLX was supposed to benefit from a newfangled project managment system called “design-build”, where the same contractor who draws up plans for the extension is also responsible for building it, in order to promote forethought and tight internal communcation. This seems so sensible that it’s almost silly to give it a name, but it’s a different world than the “design-bid-build” one that the MBTA is used to operating in. In design-bid-build, one contractor draws up blueprints for the project and hands them off to the T, which uses them to solicit bids on the construction work from other contractors. In the absence of that intermediary “bid” step as a means of cutting costs, the agency became deeply overreliant on the general contractor, a rolling ball of construction firms called White-Skanska-Kiewit (WSK), to assess the true cost of the project. When the T hired a consultant to help them assess how things had gone wrong, they were told that they didn’t have nearly enough expertise on staff to implement design-build correctly, and were relying too heavily on external consulants to perform critically budget-sensitive pieces of work. They hired a consultant to tell them that they were hiring too many consultants, successfully making themselves the butt of a suffocating office holiday party joke.

The MBTA needed about 40 or 50 fully-time staff to effectively manage the project, a far cry from the dozen or so employees who were handling it part-time. No one there understood the myriad causes of the cost increases well enough to negotiate them down, so what remained was to give up and try again, cancelling their contracts with WSK and leaving hundreds of millions in sunk cost on the table. But all was not lost! Two years later, in 2017, the agency scaled back some of the more frivolous aspects of the project, and a new rolling ball of firms styling themselves “GLX Contractors” picked up the mantle, promising to deliver the project for a billion less than the figure that WSK had quoted and putting the project on track for completion (fingers crossed) in 2021.

While the tale of the Green Line Extension has a happy ending, its epilogue is bittersweet. Imagine: in 2021 the line opens, and there’s confetti and a ribbon-cutting ceremony with cute transit-themed cupcakes. Someone updates their Green Line Bar Crawl map, and r/boston gets into a spat over whether Aeronaut Brewing is overrated. And over at the MBTA, an absolutely massive undertaking winds down and shuts off the lights. People who have spent the last five years learning how to effectively wield design-build to deliver a light rail line – how to streamline writing legal boilerplate, how to draw up exacting specifications for elevator functionality, the right person’s cell number to call when digging crews hit an unexpected utility line in the middle of the night – will go home and move on with their lives. When the MBTA next gets the wherewithal to build more rail (and it has no concrete plans to do so through 2040) all of the relationships and expertise built up on the job during GLX will have to be rebuilt from scratch, at the cost of many thousands of person-hours and millions of dollars.

Learning by doing

In retrospect, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that a transit agency with no recent experience in building light rail 2 would struggle with its first attempt in recent memory. As we’ve seen, the T doesn’t design or build extensions itself – the construction work is left to a rotating cast of construction megafirms, which in turn oversee an Yggdrasil of subcontractors and sub-subcontractors. But it also has limited input into when and where new rail lines will be built. In the Boston area, this kind of decision making is done in fits and starts by a large group of public agencies, led by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and informed by cities like Somerville, taking into account public input, budgets, state priorities, and in the case of GLX, lawsuits. Between someone saying “there should be a train here”3 and the first day of service many years later, dozens of government entities, hundreds of firms, and thousands of workers will have a hand in bringing the dream to life.

This not to suggest that the MBTA is just a conduit through which public money generated upstream is funneled into construction work downsteam. The T’s role in making GLX happen is limited, but it’s central – it makes few decisions on its own, but is a collaborator in just about all of them, giving it a chance to see opportunities and dangers that most collaborators in the project won’t anticipate on their own. The MBTA that oversaw the last few years of GLX didn’t know how to use this position to its full advantage; with its inadequate staffing and shot-in-the-dark approach to contracting, it was barely able to fulfill its own role, leaving too much of the job of cost control in the hands of contractors. But imagine that even before GLX was complete, the MBTA was already planning another rail extension, and then another, and another. This version of the agency, better at capturing successes and failures in institutional memory, would be able to bring both its bird’s eye view and the benefit of hindsight to bear in a few important ways:

Moving more planning and design in-house: it makes more sense for the MBTA to plan its own projects than it does for MassDOT, an agency whose primary focus is the maintenance of the statewide road system. And while construction is complicated enough that mega-contractors will always do most of the nitty-gritty design work, retaining domain expertise on things like track layout and power systems would help the MBTA steer these firms at a high level towards modern, cost-effective solutions. A steady stream of projects – “always having a subway under construction” so to speak – would justify these changes.4

Reducing costs by designing once: every transit project has its quirks and foibles that need special design attention, but choices of station decor, signalling components, and electrical substations probably only need to be made once. By retaining knowledge about which designs, components, and materials work well and which ones don’t, the MBTA can gradually develop a set of standards to hand to contractors. This reduces the size of decisions that need to be made, and in turn the number of billable hours, reams of Request For Procurement paperwork, expensive over-designs, and “good tries” that contractors produce.

Building lasting relationships in the public and private sector: as we’ve seen, building something like GLX requires establishing a lot of formal relationships between organizations, which on the ground really means that two people have to get cozy sending email back and forth to each other. Between two public agencies, this is as likely to prevent Parks and Rec-style infighting as anything else, but I’d argue that the real benefit here is the leverage it provides when dealing with private-sector contractors. Knowing that the MBTA has a decade or two of light rail projects in the pipeline might suppress megacontracting firms’ instincts to overcharge and underdeliver, knowing it could cost them a return trip to the buffet of local transit projects in a few years’ time.5

No half measures

Surviving the 21st century is going to require making it affordable for working people to inhabit our cities, decoupling the throughput of our economies from the throughput of our freeways, and radicially curbing our carbon emissions. This is gonna be kinda tough, and American cities need to get serious about the fact that occasional, haphazard transit expansion will not make much of a difference on any of these fronts. So what’s to be done? Maybe American planners and politicians could learn from their colleagues in Asia and Europe both the simple fact that our car-dependency is destroying the planet as well as tools and best practices for building transit to remedy the problem. Maybe we could establish a national public design agency, something like a nationalized Skanska or Fluor6 to help local transit agencies plan extensions more effectively with incentives fully aligned – after all, for many of these projects, the federal government foots a significant portion of the bill. Or maybe, cities like Boston could take matters into their own hands.

Ostensibly, the reason the MBTA has no concrete expansion plans after GLX is because it has no money. In fact, the converse is more likely to be true; if the agency had an ambition to see itself as the curator of systemwide improvements rather than piecemeal line extensions, there would be ample sources of revenue available. Los Angeles has shown us that this is the case; its Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority – “METRO” to its spin class buddies – has opened more than 100 miles of new rapid transit since 1990 in an uphill battle against a transit-skeptical, car-oriented culture. It’s done so by committing to a visionary, long-range plan, which it uses to justify keeping strong in-house planning capabilities to develop a years-long backlog of projects, waiting for federal funding to become available before pouncing on each one. And in 2016, it passed its historic Measure M by a 67-33 vote at the ballot, raising more than $120 billion by inspiring voters to help fund its vision over the next half-century.

You’re probably wondering whether METRO has become more cost-effective over time. This is a spectacularly hard question to answer definitively, and deserves its own blog post. The bad news is that they have not eliminated cost overruns: their Regional Connector downtown tunnel had its budget raised recently7 and the upcoming Gold Line extension8 will have to be shortened because of cost concerns. On the other hand, the recent extension of the Expo Line and the new Crenshaw Line have stuck to budget and are the subject of months, not decades, of delay; we can contrast this with the agency’s first foray into light rail, the Blue Line. It was built in comparable engineering condition in the 1990s, and came in 56% over budget. The mere fact that Los Angeles has four rail projects under construction today9 two decades after the New York Times crowed that the city’s first subway would likely be its last is cause for celebration. And perhaps most heartwarmingly, we can watch them learn from their mistakes in real-time, as in this cost retrospective that the agency performed between the over-budget Expo Line Phase I and the on-budget Phase II.

Do try this at home

Compared to LA, Greater Boston is much more compact, and its dense neighborhoods will respond much more effectively to improved transit – it would need only a fraction of Measure M’s new miles of rail to weave an equivalently powerful narrative. Currently, the MBTA is in the middle of comeback story; since a series of meltdowns in 2015, it’s publicly committed to improving the state of the existing system, by buying new cars, enabling more trains to run per hour, and making more stations accessible. We’re seeing real progress, though the tides of both reliability and public opinion are only starting to turn. But in five years or so, much of this work will be complete, and people will start wondering, “what’s next for the T?”10 So imagine this: in 2024, Boston commits to building a large amount of transit up front. First we draw a nice map of proposed projects, though there are so many variations on the internet that it might already exist. Then we identify a series of funding schemes: perhaps a new regional sales tax11, a congestion pricing scheme phased in as new transit lines come online12, and profitable use of the real estate purchased for new stations. Finally, we use the brand-new regional ballot mechanism approved by the Massachusett State Senate in 2018 to directly ask voters whether they want to pay for more transit. Now imagine that it passes.

More funding and grand ambition won’t signal the immediate end of incompetence and overspending at the T, but it would allow them to immediately hire (not contract out!) very talented people inspired to help them see this vision through. It would make sense for them to start with small but crucial improvements, like implementing dedicated bus lanes (something that’s been tried recently in Everett and Arlington, to great effect), fixing up the Silver Line, and extending the Orange Line through the suburbs to Needham. With a rail expansion under their belt, the T could put on its big kid pants and dare to once again tunnel through the city center, finally connecting the Red and Blue lines, and extending the Blue Line northward to Lynn13 at the same time. From there, the sky’s the limit: light rail to Dudley Square and the Seaport! Frequent and reliable regional rail! And of course the coveted Urban Ring14, providing radial transit that would eliminate the need to go downtown to change lines! The price of new transit keeps going up, so if we’re serious about using it as a tool to fight inequality and climate change – and we should be – the best time to build some was 30 years ago, and the second best time is now. If there’s a ballot initiative in the works to double the reach of the MBTA, I would like very much to be a part of it, and I have one parting suggestion: I don’t quite know how Massachusetts will name its regional ballot measures yet, but can we please call it Measure T?

- And, yeah, in Los Angeles, to build a freeway or two. Old habits die hard. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ [return]

- This is almost entirely true, but the MBTA did participate in a re-routing of the Green Line near North Station during the Big Dig, eliminating a viaduct in favor of a new tunnel. [return]

- It’s fine when other people do it, but when I try this people tell me things like “you’re blocking traffic” and “lower your voice, sir, Denny’s is a family establishment”. [return]

- New York’s MTA and its very good president Andy Byford are hoping to apply this strategy to its long-delayed project to install train control systems. [return]

- For all my incessant, boozed-up complaining about the MBTA over Thanksgiving, the agency has a solid set of crucial capital investments in the works as we speak. Arguably the most important of these is procurement of new Red and Orange Line cars to replace the current fleet that is far past its projected service lifespan. Ordering the Red and Orange fleets simultaneously from CSR Sifang is a baby step towards leveraging economies of scale, since the design of the cars is mostly the same. As they inevitably break down, catch fire, and get surfed on in the coming decades, having a common set of parts and a larger pool of mechanics to fix them will help the agency do more cost-effective maintenance. [return]

- Or we could, you know, nationalize Fluor. [return]

- This project has suffered in particular because it runs through the heart of downtown LA and has had to content with a lot of unknowns regarding the utility lines in the area. A public official was quoted as saying the project has become about 6% a construction project, with the remainder being a utilities project. [return]

- One of the reasons cited for the increased cost of the Gold Line is a seller’s market “flooded with rail project proposals” which is, well, a good problem to have. [return]

- I’m counting the Regional Connector, Purple Line, Crenshaw Line, and 2019’s impending Blue Line rebuild. [return]

- Recently I attended a Q&A session by this exact name with MBTA Fiscal Management and Control Board chairman Joseph Aiello. He was rightfully excited about impending plans to modernize the Orange, Red, and Green lines, but noncommital about any major plans for new contruction like the North South Rail Link. [return]

- One percent of the state sales tax already goes to the MBTA, but has failed to provide the revenue that lawmakers anticipated when they put it in place. A regional funding mechanism would be a tax only on the areas that would see improved service, and would require the T to carefully sell their plan to each municipality in the Boston area. [return]

- Los Angeles may beat us to that punch as well. [return]

- Er, actually could we make it to my grandma’s house in Salem? [return]

- My precioussssss [return]