Closing the gap, opening the region: the North-South Rail Link

Imagine for a moment that your city lacked a highway network entirely. Instead, it had a series of ordinary two-lane streets in place of Interstates X, Y, and Z, each with massively wide turns and hundreds of feet of totally undeveloped grassland on each side – in short, everything that a highway implies except the pavement. The roads don’t connect downtown, but lo, there is an pre-excavated tunnel under the city center that we can use to connect them. There would be no debate about whether to build highways on this land. It would have unanimous political support. You and I would be sleeping in hard hats and driving backhoes around right now racing to get this project done last week.

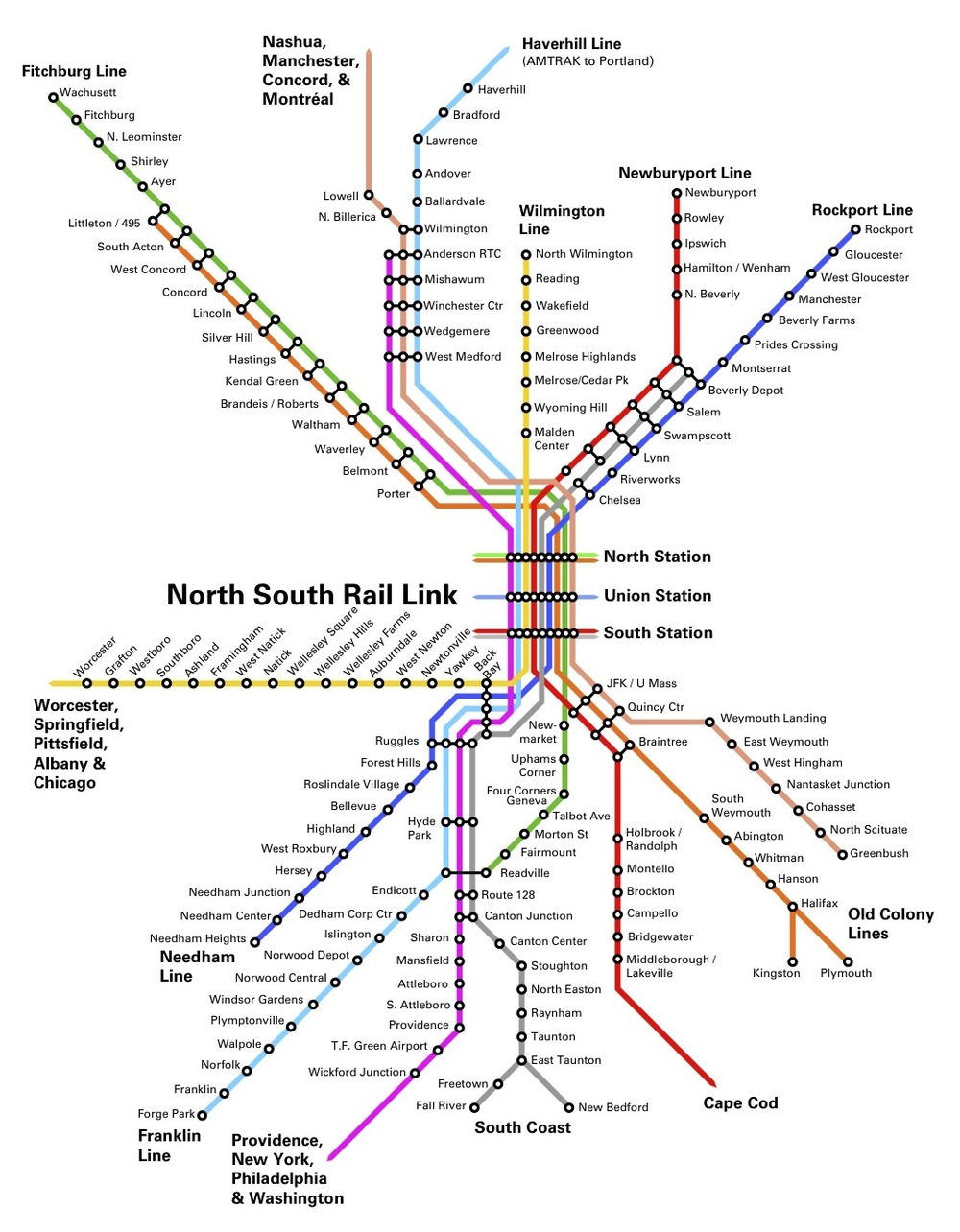

I’d like to suggest that Boston’s existing MBTA Commuter Rail is quite like these massively underused interstates-to-be. Its 398 miles already cover massive distances and carry about 100,000 daily riders1 to many of its outlying communities, but with sparse train schedules that barely scratch the surface of their amazing potential. Adding capacity to a railway doesn’t much resemble adding lanes to a highway – rather than adding parallel tracks, it means buying better vehicles, improving stations, and running more trains. Just like our hypothetical roadways, the Commuter Rail is split into two entirely disconnected halves terminating about 1.5 miles apart and branching out in opposite directions from North and South Stations. But luckily, there is nothing metaphorical about the pre-excavated tunnel under the city. During the Big Dig, we cleared a path between North and South Station of all kinds of utilities and spooky archaelogical surprises, and filled it with loose earth, waiting for Boston to regain its appetite for tunneling and connect the region in one fell swoop with a project we call the North-South Rail Link.

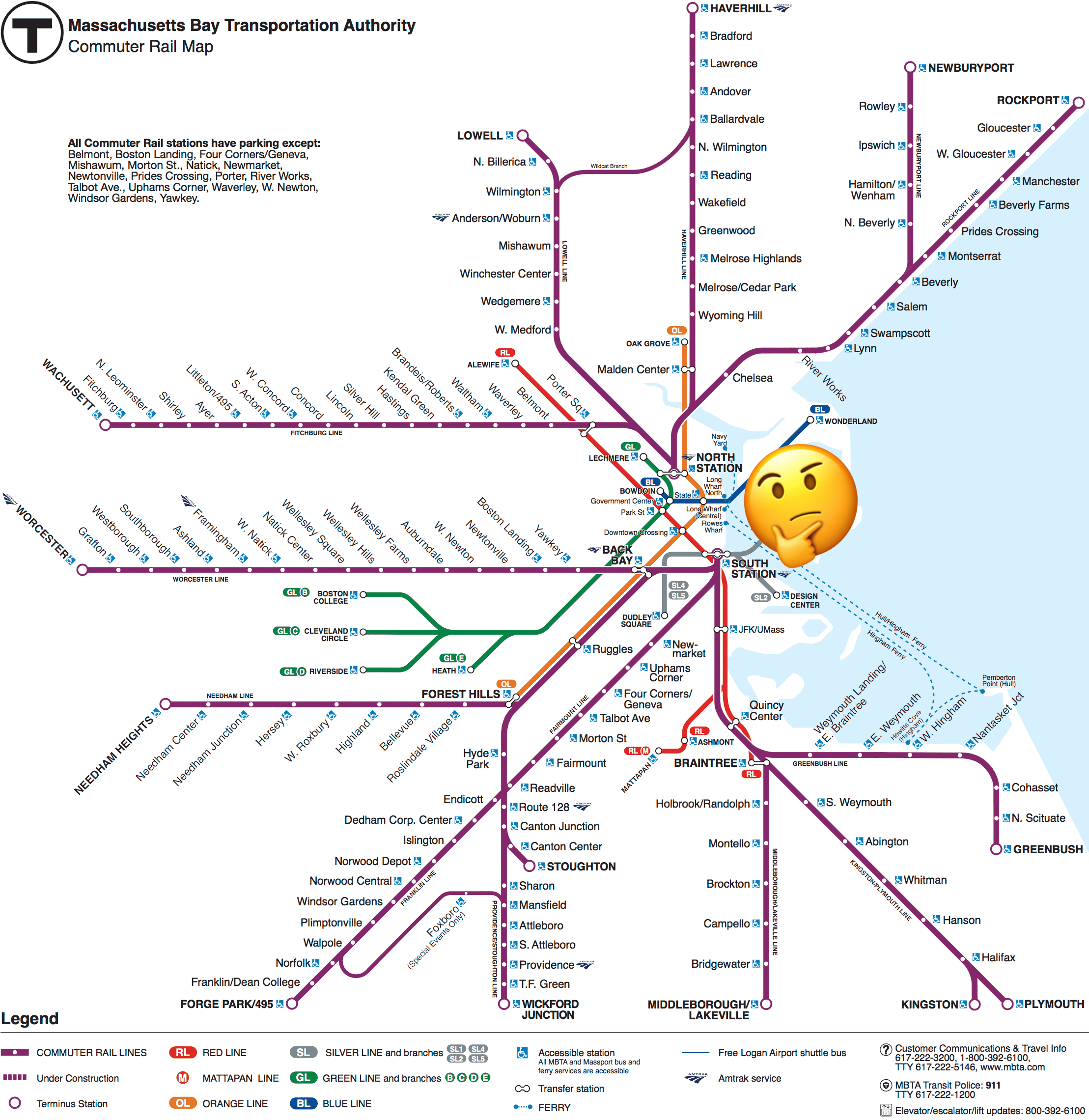

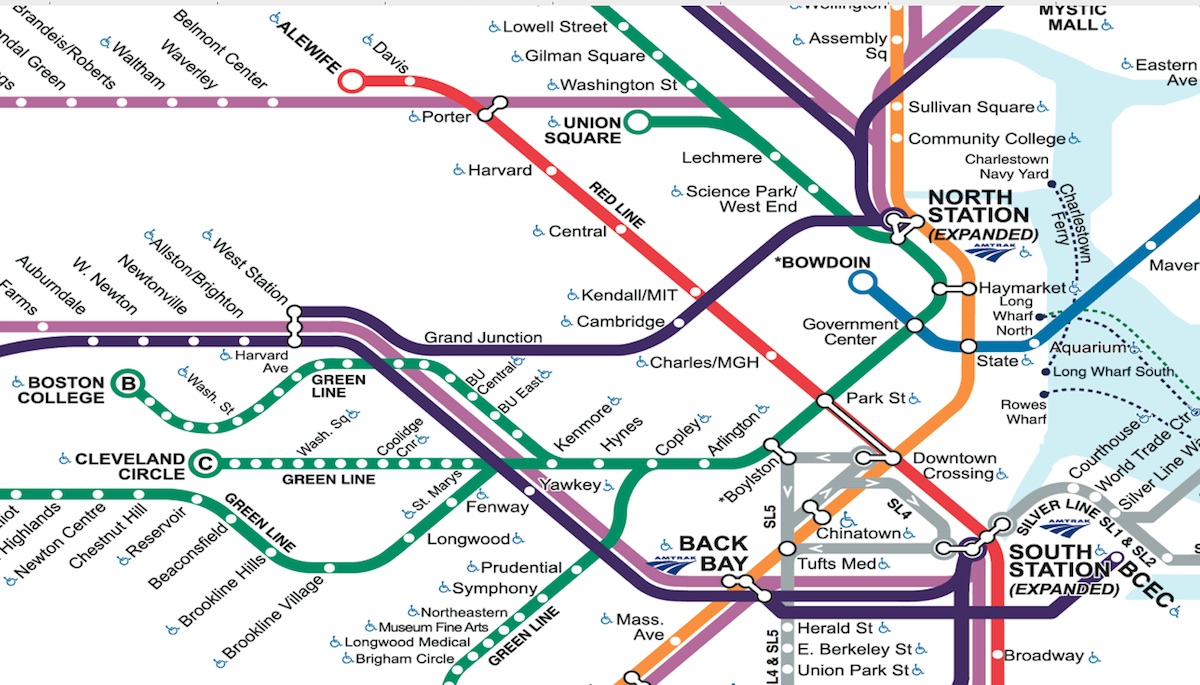

Just from a glance at our subway map, the benefit of the North-South Rail Link (NSRL) is evident. Getting from North to South Station requires two, count ‘em, two subway transfers, making commuting into and then out of Boston on the Commuter Rail the kind of journey Tolkien wrote about. You can imagine that almost nobody does this, and that this service gap contributes to Greater Boston’s north-south cultural divide. On its face, digging a tunnel between North and South Station offers some clear advantages over the existing network’s structure:

- Commuters can ride the Commuter Rail clear across the city and access jobs that would be otherwise impractical to reach by transit, and a pain to reach by car.

- MBTA operations become a lot more efficient, since the trains and equipment belonging to the two halves of the network are no longer isolated from each other.

- The ride from North to South Station would become faster even for people travelling within downtown.

But with a price tag between $4 and $6 billion kindly estimated by the wicked smaaht folks up at Harvard, it’s crucial to understand that rationale for building the Link goes way beyond getting commuters from North to South Station – it’s about enabling a better kind of rail service on the strong skeleton the Commuter Rail provides. When a small but growing group of NSRL advocates like Congressman Seth Moulton say that the project would add 100,000 new daily trips to Boston’s rail network, this is what they have in mind. This vision is hard to compare to any existing system in the United States, but far from being a new idea, it falls into a well-established pattern of rail service in Europe and Asia. So to really understand why Boston should build the NSRL, let’s book the cheapest WOW! Airlines flight we can find2 and make our way to the transit Mecca of Berlin, Germany.

An old, new kind of rail system

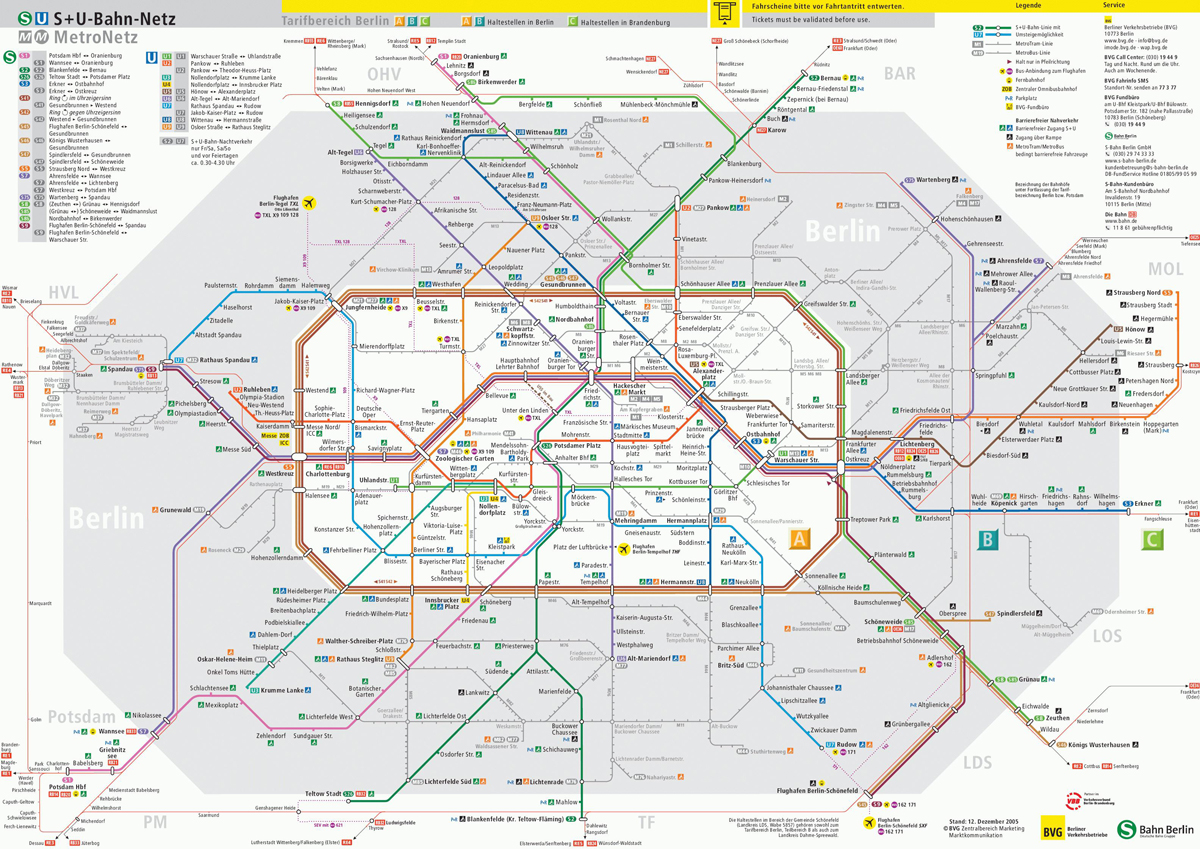

Assuming your WOW! flight ever gets off the ground, you won’t get far in Berlin before spotting this practical, unfussy map of its rail network:

“God damn”, you say loudly, outing yourself immediately as an American tourist. “That’s a big subway system!” It turns out you’re about half right. While the subway, or U-Bahn, is fairly extensive, most of the lines on this map are an altogether different system called the S-Bahn. This network extends farther outside of the city and stops less often than the subway. But beyond that, it’s pretty similar – it runs electrified trains, uses tunnels downtown, works with the same fare system, and, especially on the central “trunk” where many lines converge, has frequencies that rival the U-Bahn. The experience of catching an S-Bahn train isn’t fundamentally different than riding the subway, which is reflected in this map that makes them hard to tell apart. This blurring of lines between rapid transit and regional rail is crucial to enabling the walkable communities that Europe is known for, and is exactly what we should be attempting to do with the MBTA Commuter Rail.

“Pshaw”, you reply, between mouthfuls of currywurst, “That May Work In Those Countries, But It Would Never Fly Over Here™!” Yet Greater Boston has all the ingredients required to support a Berlin-style regional network. Many outlying towns in the area predate archetypical car-oriented American suburbs by centuries, and have a walkable and mixed-use core ideal for increased transit frequency. Places like Waltham and Salem already have vibrant downtown areas and are building high-density, transit-oriented housing near the commuter rail even in the absence of any major improvements to the system. Introducing respectable train frequencies into these systems would kick off a virtuous cycle of more walkable development, more housing, and more commuting options for everyone, all of which would make my stupid lefty heart swell with pride, but more importantly would massively expand the list of places with frequent transit service to Boston and relieve our housing market.

For some of these communities adjacent to the Commuter Rail system, an upgrade is long overdue. The Fairmont Line runs through dense and transit-dependent areas of Boston that would massively benefit from more frequent service. The Newburyport/Rockport runs through working-class areas of Chelsea and Lynn, where recent immigrants and longtime residents alike struggle to efficiently commute to their jobs in Boston. The new Boston Landing stop and coming West Station on the Framingham/Worcester line, if served frequently enough, would bring rapid transit to areas of Allston served either reluctantly or not at all by the Green Line. The benefits would extend even to people who commute strictly within the city, as the new service pattern would effectively create a new subway line for downtown Boston, allowing riders to travel between North Station, South Station, and Back Bay with unprecedented ease and relieving stress from overcrowded transfer stations. In a growing city, the alternative to this solution is not “do nothing” – if we don’t upgrade the Commuter Rail, we’ll need to find other, more expensive solutions to serve these areas properly.

Capacity for the next century, not decade

Even understanding the benefits that S-Bahn style service would provide to Greater Boston, but it’s fair to ask why we need the NSRL to enable this – can’t we just run trains more frequently on existing tracks? It turns out that while we could run more trains than we do today, the shape of our current network makes it impossible to scale up to true Euro-style regional rail. There are many reasons why Commuter Rail trains run infrequently, in particular the cost of staffing, but the biggest problem is that you can only fit so many trains into a complex terminal like North or South Station (what we’d call a “stub-end”) at a time. Movement into and out of a stub-end platform must be done slowly, and in practice about 30% of train movement in these stations is made by trains entering or exiting service, not carrying passengers. The pace of movements through a railyard would best be described as “trundling”, and so the last few hundred yards of an inbound Commuter Rail trip seem to take up a disproportionate amount of time.

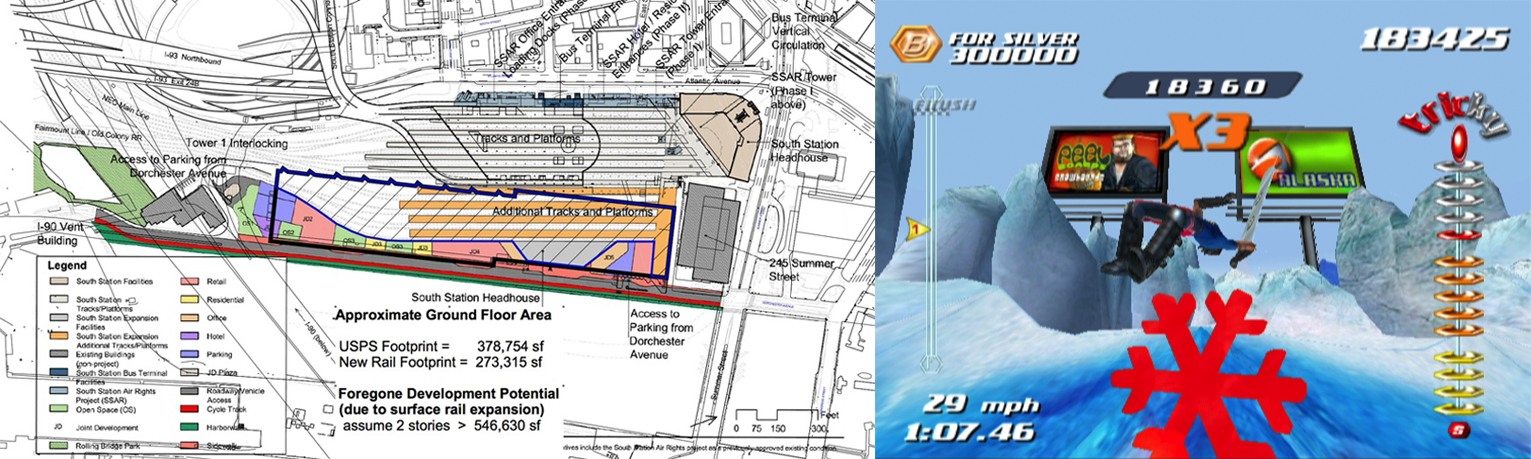

Determined as ever to sorta kinda do the right thing, the MBTA is currently planning the South Station Expansion (SSX) project to add seven new tracks to South Station at the cost of about $2 billion. This project would replace the existing Post Office building along the Fort Point Channel to increase the capacity of (half of) the Commuter Rail system. This is a fix to our capacity problem in the same way that Pimp My Ride was a fix for many a barely-functioning Pontiac Grand Am. “Yo, I hear you like trains”, Xzibit gushes, bursting on set in striped overalls and a railroad engineer’s cap, “so we put even more trains on your incredibly valuable waterfront real estate!” Instead of fixing the underlying problem of train movement and storage, we’ll quickly run up against South Station’s expanded capacity in a decade or two, only this time with nowhere to expand to. By contrast, connecting North and South stations removes the stub-end bottleneck, allowing commuter trains to pass through the core of the system and terminate somewhere on a branch line in response to demand.

There are some secondary improvements that the a well-planned NSRL would enable as well. Like your toothbrush, any trains that run through the Link would have to run on electric power rather than diesel due to the problem of ventilating toxic fumes. This means they would accelerate faster and reach their destinations more quickly than the existing locomotives. Retrofitting all platforms to permit level boarding (aligning platform and train heights to eliminate flip-out boarding staircases) would reduce the duration and improve the predictability of stops, since passengers with limited mobility would find embarking and alighting much easier. Electric trains don’t have a locomotive pushing or pulling the trainset – instead, each car has its own onboard propulsion drawing from an overheard wire or third rail – which means it’s much easier to configure smaller sets of cars together for off-peak service, as will be possible with the new vehicles coming to Caltrain that will carry thousands of passengers and their loud phone conversations about their startup’s top-secret IP up and down Silicon Valley.

The cost savings of short dwell times, sharing equipment system-wide, and being able to flexibly decouple, route and terminate trains will quicky add up. A 1995 study suggested that building the NSRL could save the MBTA about $140 million (2017 dollars) in annual operating costs 3. Most importantly, they will no longer have to drag trainsets loudly past my old house at three in the morning on the lone Cambridge freight track that connects the two halves of the system. Before it’s too late, Boston and the MBTA need to figure out what dozens of cities around the world have long-since learned – nothing provides capacity or operational flexibility like running trains through the urban core.

Organization, electronics, and concrete

Knowing what we know about the Germans, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that they have a pithy and pragmatic expression encapsulating their philosophy behind running trains. Organisation vor Elektronik vor Beton (“Organization before Electronics before Concrete”) is not just the name of my industrial rock project but a maxim that serves as a kind of checklist4 for transit planners deciding what kinds of investments to make:

First, improve your organization: schedules, routes, and policies, to be as efficient as they possibly can be.

Then, ugrade your electronics: fare collection, power, train control, signaling, and communication systems to get the most bang for your buck from the existing track-miles of service.

Once you’ve maxed out these other strategies, and only then, should you spend money on concrete: new tracks, bridges, tunnels, etc.

These are listed in increasing order of cost – improving organization will often net a transit agency some savings, while building new track miles is a multibillion dollar affair these days. That’s why the NSRL must be viewed as a platform for better organization and electronics, not just an expensive piece of concrete. The tunnel itself is crucial, but planning for every other part of the new system should begin before we break ground. The current fare collection system, whereby a conductor checks everyone’s ticket (or tries to) needs to be replaced by pay-on-platform. Negotiation with operator’s unions needs to begin far ahead of time, so we’re not overstaffing modern trains just to comply with union regulations. At a system level, we should decide early what kinds of service patterns to implement and what level of service the stakeholder communities will receive, and make some tough decisions about routing. There are simply more branches running from South Station than North Station, so certain trains will still terminate in the surface yards of these stations.

With a concrete-only mindset, there is a real danger that we could spend many billions on the Link and never use it to its full potential. Such a thing has happened in Philidelphia, which built its Center City Commuter Connection to solve a suspiciously similar problem in the 1980s. While the network is extensive, connected, and fully electrified, myopic management and staffing practices have prevented the system from even approaching its maximum service frequencies. If we’re not commuted to running a North-South Rail Linked MBTA in a way that respects the size of the investment, we should forgo building it and continue writing a wistful Globe op-ed or two per year about the project instead. But I want to believe that we won’t back down from the challenge.

Could this really happen?

Yes, but our window of opportunity is closing – if we go through with South Station Expansion, the political will to invest billions in the Commuter Rail will dry up for a few decades. At that point, there’s a realistic chance that new construction will have blocked the underground pathway between North and South Station, permanently preventing a link between the stations (also, it’ll mean that I’ll probably be dead before the damn thing is finished). Money is, you know, a factor. The $4-6bn for the Link itself and another cool billion or two for new rail cars, branch electrification, and station moderization, are going to have to come from somewhere. But a project that touches such a wide swathe of the Boston area, adds so much ridership to the system, and nets us a new high-capacity transit line downtown could draw support and funding from a wide network of communities and government agencies. Especially when viewed as an alternative to South Station Expansion, it’s a startlingly cost-effective investment.

The North-South Rail Link may be unique among United States transit proposals in its ability to transform not just a corridor or a city but an entire region, commiting us to a more equitable and connected version of the urban fabric that makes the Boston area such a wonderful place to be. Opportunities like this are like off-peak Commuter Rail trains – they don’t come often, and we’re not going to want to wait around for the next one.

- Indeed, the system carries 42% of commuters at the peak of Boston’s rush hour. [return]

- I really recommend that you do not do this. [return]

- Check out table EX-3 on page EX-10. Or don’t – I’m a footnote, not a cop. [return]

- OVEVB an interesting way to gauge American transit projects, like your local streetcar to nowhere. If you read about a project in your area that doesn’t follow these principles, be sure to write an angry letter in German to the planning agency and they’ll probably be obligated to publish it in the public comments section of their environmental impact report. [return]