Whose line is it, anyway?

A housing project — maybe a tower, some condos, or a whole new neighborhood, is in the news. Proponents are excited at the chance to add more housing (near a new transit line, no less!) that will help address the region’s ballooning rent prices. Detractors are worried that the project will cause rents to skyrocket in the area, displacing the current residents. Who’s right? Mathematically, at least, there’s no reason they both can’t be. To illustrate this, I’ve created a little visualization below. We’ve just added six new units of housing near a transit line in idyllic, uh, Trainsville. What effect do they have on housing prices? At what scales? Resize the radius of interest and see for yourself, and keep this (over)simplified demonstration in mind as you read.

In California, we’ve been having this conversation for a while. In January 2018, state senator Scott Weiner introduced SB 827, a bill that aimed to address the state’s alarming housing shortage by legalizing the construction of higher-density housing wherever there is a nearby transit line, superseding local zoning codes. Had the bill passed, almost the entirety of San Francisco, along with large swathes of the greater Bay Area and Los Angeles, could have become home to eight-story apartment buildings (later reduced to five), constructed without minimum parking requirements. While the bill as written frankly never stood a chance and died a quiet death surrounded by loved ones in commitee, it highlighted a diversity in pro-housing viewpoints that we would do well to better understand before another similar bill hits the floor.

Supporters predictably included the YIMBY (“Yes In My Backyard”) housing activist group and a whole bunch of urban planning professors1. But perhaps surprsingly, there were many vocal detractors from the left — most notably LA’s chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), who voiced their opposition in a comprehensive critique of the bill. They identified ways in which market-oriented approaches to housing development like SB 827 at best treat the specific needs of poor and working-class communities as an afterthought, and at worst can displace these communities to make way for expensive developments. Deep in this analysis is a statement that I’d like to highlight:

We must have a more nuanced understanding of housing markets and move past the inaccurate belief that “more supply of any kind leads to lower prices.” There are different spatial scales we must consider. Development in a particular neighborhood could marginally bring down prices across the region while sharply increasing rents and risk of displacement in the areas immediately surrounding.

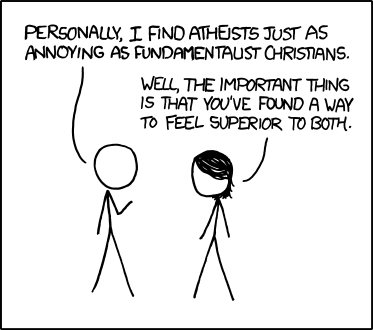

More awareness of this fact during conversations about the housing crisis would lead to less disagreement, or perhaps clearer agreement on what we’re disagreeing on. And who’s we anyway? For those of you new to the sport of full-contact California housing advocacy, here’s the score:

Center-left groups like YIMBY focus on the housing crisis through a regional, market-oriented lens, advocating for more permittive zoning regulations everywhere and shouting down homeowners who don’t want anything built that might cast shade on their petunias. This group hopes to leverage massive amounts of new housing supply, as well as negotiation with private developers, to make housing more affordable.

Leftist groups like DSA take a, well, socialist view of the problem at a local, neighborhood level, fighting for better rent control, and brand new tenant protection measures like right-to-counsel. The DSA is very reluctant to show support for market-driven housing development, preferring to advocate for public housing wherever possible, though the pace of its construction locally remains absymally slow.

Here’s the upshot: both groups2 are using different tools to solve different problems at different scales – each I’d argue, using the right tools for their respective jobs. My hope is that in the coming years, an SB 827-like bill that both camps are satisfied with can gain broad support among housing activists, and ultimately make a big dent in a state that desperately needs more rapid transit, more housing, and much more of each near the other.

Here Comes the Neighborhood!

The best rapid transit plan is a good land use plan, which is to say that it’s easiest to build transit in walkable, urban places. In America, though, transit lines are often built across sprawling metropolises, running through neighborhoods full of single-family homes from downtown to the airport or the hellmall or whatever. In an effort to kickstart a walkable neighborhood in these places, dense housing and retail developments are often planned near these intermediate stations — a strategy we call Transit Oriented Development or TOD. For some transit projects, TOD is a value-add; for others, it borders on being the justification for building the whole thing. Regardless, American TOD tends to look out of place in its larger context. It usually consists of apartment buildings in a modern “cookie cutter” glass and aluminum style that everyone seems to hate, with new retail catering to the kind of professional who you’d expect to live there. Because TOD often relies on an exception to the local zoning code, it’s also built markedly taller than the surrounding blocks.

Even when thoughtfully integrated into an existing neighborhood, TOD can smell like the end of affordability in an area, much like goat yoga studios, driftwood jewelry boutiques, and a food critic gingerly dispatched by the local paper to declare the area safe and “desirable” for white people. Because of the sheer number of shiny new units that it brings, TOD can easily raise the average price of an apartment in a neighborhood. At its worst, TOD is the physical embodiement of the anti-density strawman that wantonly displaces whole blocks full of “regular” people to make room for young professionals who kinda want to take the train sometimes.

The fear that new development near transit is ultimately displacing people who need transit to make room for people who like transit is a growing concern. A widely-circulated LA times story from early 2018 even linked developments along LA’s Purple and Expo lines, and correlated increases in adjacent real estate, to falling ridership on Metro. The people who can actually afford to live near the train are, paradoxically, the ones least likely to make full use of it. In transit industry jargon, these are “choice riders” – ones who consider transit an amenity in the same vein as a nearby Equinox club. They’ll use it when it’s convenient, but certainly don’t depend on it, and will probably opt for Uber or Lyft before transferring to a bus.

Pictured: Todd near Los Angeles’ Red Line (I’m not sorry)

Actual data about this phenomenon points to patterns and trends more than straightforward cause-and-effect — one study from UC Berkeley shows clear correlative relationships between new rail transit and displacement near stations, but in 415 pages of analysis still sort of throws its hands into the air and says, “shit’s complicated”. Another, slightly more understandable report from the University of Minnesota looked for signals of displacement near new rapid transit lines in ten North American cities and found no significant indicators for about half of them (including Los Angeles’ Expo Line, which has been the source of much such consternation).

So while transit isn’t built for any demographic in particular, we should recognize that the marginal utility of living near a rapid transit station for someone who is going to use it every day is greater than for someone who views it as an amenity that will help them beat traffic twice a year on their way to the Big Game. Without understanding and managing the interaction between transit and displacement, we run the risk of replicating in our cities the problems that plague transit in the suburbs: low ridership causing funding cuts causing low ridership in a death spiral that limits everyone’s mobility, but disproportionately so the working class.

A different story at a different scale

The usual story of gentrification has birthed a thousand SF open-mic jokes and has a Guess Who? board of classic characters: the yuppie artists, garage coffee shop proprietors, luxury housing developers, and corrupt aldermen whose machinations turn a neighborhood with a century of history into a souless nowhere. But as a lens for understanding why entire metropolitan areas are so expensive, it puts the cart before the horse (or, uh, the pedicab before the white guy with dreads) by failing to account for why so many wealthy people want to move into certain affordable neighborhoods in the first place: the commute.

Cities like SF, Seattle, and Boston are adding jobs much faster than they’re building housing or transit – in San Francisco it’s something like six new jobs for every one new unit of housing, and Boston has built roughly zero miles of rail for every fuckton of new arrivals over the past three decades. Simply put, there isn’t a home in the city for everyone who wants to work there. Not even close3. So the radius of what constitutes an acceptable commute expands — in SF, far outside the city and even past the reaches of the lengthy, if sparse, BART lines that extend through the East Bay. People working minimum-wage jobs in San Francisco (you know, where the jobs actually are) are spending three hours one-way just to get to their jobs via transit.

Zoomed out at this level, inaction, not development, appears as the obvious driver of displacement. When it’s normal for people across all income levels travel an hour each way to work, the primary amenity of a neighborhood becomes the promise of a reasonable commute. Areas along transit lines and near freeways, once avoided by those with the means to do so, become more attractive and even their old and decrepit housing stock becomes very expensive. This helps explain why filtering, the process by which older housing stock gradually becomes more affordable, is happening much more slowly in California than elsewhere4. While protections like rent control can help keep existing residents in these neighborhoods on short timescales, they’re fighting a long-term uphill battle against newcomers eager to take the train to work who will have no problem making rent — and the businesses eager to move in and serve them.

Aside for my CA friends: California’s rent control laws, written in fountain pen by a man twirling his moustache, are a real kneecap to long-term affordability, they allow landlords to raise rents back to market value when an existing tenant leaves, and ban rent control on any building constructed after 1995. They’re up for repeal in November! Go vote!

One of many solutions: build out the missing middle

Okay, deep breath. Hopefully the takeaway from hearing these different stories is not that one or the other is wrong, but that we need to hear both to fully grasp the extent of the problem. At a local level, tenant protections like rent control and right-to-counsel can make an enormous difference in individuals’ lives. Knowing that housing prices are projected to dip in a decade or so is very cold comfort to someone who is being priced out of their own neighborhood this year because a light rail line is opening. But at the same time, cities change and grow, and wishing that time would pass your city by is both fruitless and a terrible curse in its own right. To reverse decades-long, regional planning mistakes like, uh, the whole concept of Silicon Valley, the first, obvious step needs to be simply legalizing the production of more housing in the way SB 827 proposed.

Outcry against housing development is often focused on tall, ostentatious projects that appear comically out of place in their larger context. This is a valid point, but it’s usually made for the wrong reasons. Rather than never building anything denser than single-family housing, we should aim for a smooth, natural transition between sparse, single-family housing and dense high-rise development. This is often referred to as “the missing middle” of housing development — concretely, it looks like multifamily housing like fourplexes and apartment buildings up to perhaps four or five stories tall. Housing activists can sometimes do a poor job of communicating this, but the missing middle, not luxury condominiums, is ultimately what we want to see constructed to quell the growth of housing prices. The problem is that zoning laws simply prohibit this in many places, which means that the 40-story condos (or TOD built on zoning variances) are what remain to advocate for…or against. Long-term proposals like Minneapolis’ 2040 Comprehensive Plan seek to address this, and fighting for the missing middle in the sparsely-populated neighborhoods that cover most of San Francisco is a primary focus of SF YIMBY.

I’d also argue that there’s a corresponding “missing middle” of transit that needs to be built in concert with this new housing as well. When transit-oriented development is exclusively centered on rare, expensive, over-glorified rail projects, it becomes a rare opportunity to be answered with “visionary” development projects near stations, and the pressure is on to make things taller, glassier, and ritzier. When cities invest commensurate amounts of energy into building out frequent, understandable, comfortable bus service (I finally get to link back to my own post! I’m a blogger!), there are many more opportunities to build TOD that fits in seamlessly in scale and price with the immediate surroundings. Blanketing a city with a reasonably useful rapid bus network with dedicated right of way and well-planned transfers (and enough drivers! C’mon, Muni!) is key to reducing the extent to which high(er) quality transit like BART blows up rents near its relatively few stations.

Building more housing near transit in urban areas isn’t just making room for more people; it’s righting a historic wrong. American cities, San Francisco foremost among them, face displacement of people of color and the working class in part because most homeowners (and thus many landlords) are the middle-class white families who were able to purchase homes before renewed investment in cities caused real estate values to skyrocket. We no longer have the redlining policies that denied home loans in certain areas to nonwhite people, but we now have homeowners’ associations hell-bent on preserving the “character” of neighborhoods by keeping out dense multi-family housing that might slow the surging of their property values.

In the Bay Area, a place to live isn’t a given, it’s certainly not a right — it’s a scarce resource kept close to the chest by those who have been holding all the cards for decades. The poorest among us are dying in the streets, and even for those with comfortable tech jobs, homeownership isn’t a realistic goal — it’s an ironic joke with a punchline about earthquakes or avocado toast. I don’t want to live here — I want to live in a version of this place that welcomes many more people and offers them reasonable, affordable commutes. If nothing else, SB 827 was a start of a rousing conversation about how to get from this world to that one, and I hope we’ll keep talking to each other, not over each other, to make sure it’s not the end.

- Not sure what the demonym is here. A “correlation” of urban planning professors? a “metropolitan statistical area”? [return]

- Disclosure: I am a dues-paying, though not particularly active, member of both organizations. [return]

- Heartbreakingly, there probably is a vacant apartment for every homeless person sleeping on the streets of San Francisco tonight. Unfortunately, if we seized all vacant apartments in the city, we’d quickly be back in the same situation we’re in now because of induced demand; we don’t just need better redistribution, we need more of a very valuable resource. [return]

- For a demonstration of this, you’re welcome to visit my very old, very expensive SOMA apartment, which is built on a roughly 3-degree slant. Even as I write, my swivel chair is rolling back towards the waaaaa [return]