Boston's Red-Blue Connector is about fixing the core system

When transit advocates in Boston call for expansions of the T, the response from MassDOT and Governor Baker is that we first need to focus on fixing the core system — making sure that the vehicles, stations, and track we already have can operate at maximum efficiency. While this can sometimes feel like a “shove off, we don’t have the money”, it’s a pragmatic stance, and to their credit, the MBTA is actually in the middle of a push for such investment, with orders for new Red and Orange Line cars in the works and improved signaling and winterization schemes in the pipeline. By and large, prioritizing maintenance over expansion is a sound principle and I am not here to challenge it. Instead, I want to dig a bit deeper into the assumptions made when dichotomizing capital investments into “expansion” versus “maintenance”. Broadly speaking:

Expansion means new revenue service to new places, adding new transit users to the system and putting additional stress on existing infrastructure. We can’t “do” expansion right now because it would be unsustainable and irresponsible to redirect resources to new parts of the system when existing ones are not being adequately maintained.

Maintenance means making investments that will allow us to more effectively use the infrastructure we already have. It means updating outdated technologies like fixed block signaling that don’t take advantage of modern communication systems and fixing historic mistakes (oh god the Type 8’s) that have caused inefficiency to creep into the system over time. Generally speaking this means not adding new riders per se, although it might increase the overall capacity of the system. Capital investment in this category must be ongoing and sustainable, and we have a lot of backlog here to slog through before we can think about “expansion”. Specific examples include: modernizing signaling systems, replacing rolling stock, cleaning and modernizing stations, etc.

This distinction has found its way into a lot of discussion over transit investment in Boston and other cities with legacy systems. I wish to pose the question of whether a project might exist that is incorrectly categorized as reckless expansion when it actually lives much closer on the spectrum to “sound maintenance” projects like new signaling systems and the Government Center overhaul. I think the Red-Blue connector is such a project.

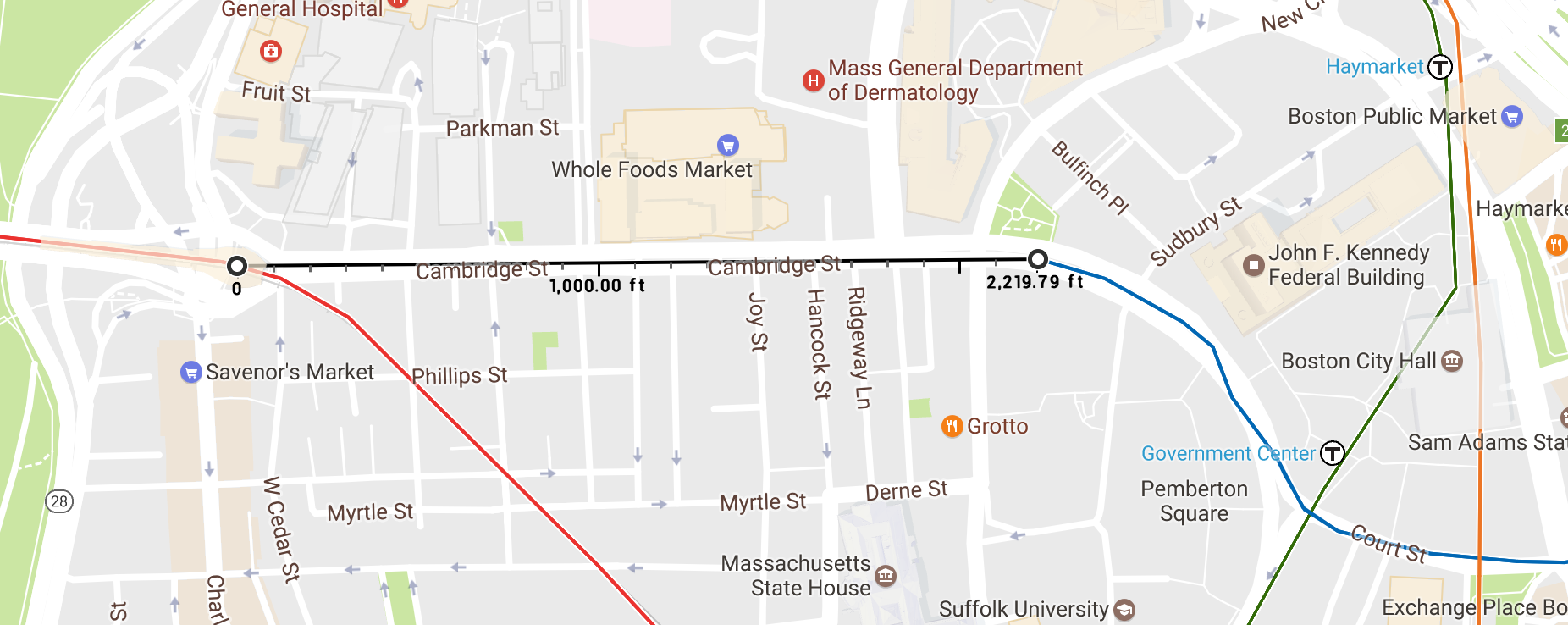

The distance between Bowdoin, the Blue Line’s current terminus, and the Charles/MGH Red Line station. Let’s all stare at this image and collectively will the black segment into existence.

The fact that the Red and Blue lines don’t connect – even though the Blue Line terminates about 2,000 feet from Charles/MGH – is a head-scratcher for tourists, frustration for commuters, and increasingly, a bottleneck on the capacity of our core subway system. Though the state was made to study the option as a Big Dig mitigation project, it was deemed too expensive and shelved, though the $750 million price tag given by MassDOT is for an absurdly over-engineered version that would make it the most expensive piece of subway per mile in the nation.

Whatever the actual price of construction, the cost of ignoring Red-Blue is becoming increasingly apparent as our core stations groan under the weight of over 100,000 daily transfers1. Because of its absence, commuters treat the existing downtown transfer stations as a sort of superstation where the Green and Orange lines serve as a glorified moving walkway2 to get between Red and Blue platforms. The increased footfall puts stress on stations like Park Street and Government Center and overcrowds the barely adequate Red, Green, and Orange line cars while the Blue Line cruises around far under capacity downtown. This crowding has ripple effects throughout the system; at a Kendall Square Mobility Task Force meeting I attended (awkwardly sat in the back of and ate four oatmeal cookies) it was mentioned that the variability of train dwell times at Park Street is a primary bottleneck for throughput on the Red Line. Extending the Blue Line about half a mile would improve the capacity of every other subway line in the system by better balancing the flow of downtown commuters throughout existing stations. It lets us use our existing infrastructure more effectively — sounds familiar, no?

I want this on a shirt, but no one will print it for me because trademarks

A Red-Blue transfer is not a “would be nice someday” like the North-South Rail Link or a Green Line connection to the Seaport. It’s not even an I Can’t Believe It’s Not Built Yet™ in the same vein as the Blue Line to Lynn. The fact that these two lines don’t connect is a fundamental shortcoming of the topology of our subway network. When Governor Baker and the Fiscal and Managment Control Board triage the problems that the MBTA faces today, the Red-Blue connector needs to be bucketed not with other subway extensions, but with issues like vehicle procurement and signaling upgrades, and maybe just a notch below “the trains are literally on fire”. It’s an embarrassment that deserves our full attention the moment the Green Line Extension checks clear.

- This is the total number of Red-Green and Red-Orange transfers as given at the bottom of page 16 of the 2014 MBTA Blue Book. [return]

- Hong Kong has an actual moving walkway between its adjacent Central and Admiralty stations, and it’s pretty cool. I have been told by folks at the T that an equivalent connector between State Street and Downtown Crossing is probably impossible due to the geometry of the stations. [return]