Now this is podracing!

Another year, another startup claiming to have solved urban congestion — this time it’s Arrivo, which has announced “the end of traffic” and dropped a slick video of their vision for travel in the 21st century, involving private vehicles loaded onto maglev pods and rocketed along highway medians at 200 miles per hour. A surfer dude pulls on a wetsuit at Mach 0.25 before we jump-cut to the beach in time for to shed some early morning gnar. A woman smiles in delight as her pod informs her that she has been TSA pre-checked, presumably having automatically disposed of her favorite water bottle for containing too much liquid. There’s a tantalizing multimodality to the video; connections to existing transit are emphasized and it appears that some pods can be boarded on foot and linked together like (very) low-occupancy trains. On Product Hunt it is described, alas, like “if Hyperloop One AND Elon Musk’s The Boring Company had a baby.” In fact, by inbreeding Ol’ Musky’s two paper-napkin concepts of future mobility they’ve managed to extract the worst parts of each: the Hyperloop’s uphill battle to productionize maglev technology and the Boring Company’s cars-on-a-pod idea with its fundamental capacity constraints.

Startups like Arrivo are fixated the promise that vehicles with enormous top speeds will lead directly to faster travel times in urban areas. This is apparent in their specious claim of a 35-mile journey through Denver in <10 minutes, which is possible only if the vehicle is moving at top speed for the entire journey and accelerates at bone-liquefying rates. Passing off your proposed maximum speed as an average speed to professional journalists is great fun, but how fast your hyper-sled-pods can move is really the less important half of the puzzle. A related but much more revealing question is: how many pods can you run?

For a system that interfaces with an urban street network, the answer turns out to have very little to do with top speed. Arrivo founder Brogan BamBrogan1 claims that his proposed network can carry 20,000 cars where a normal freeway lane could handle 2,900-5,500. Put simply, this estimate is only in the ballpark of accuracy if you ignore the fact that vehicles need to exit the system. Low-occupancy vehicles that merely zip along an infinite highway can be very fast but aren’t all that useful; eventually, their occupants want to get somewhere interesting where they can park their vehicle, walk around, and live their lives. In other words, they want to merge into urban traffic. The choke point where your podracing network meets the street where you have to drive yourself around like a pleb will function just like a highway off-ramp (plus a pod unloading stage), and the number of vehicles that can perform this process per hour will ultimately determine how many vehicles can utilize your network.

Laundry, latency, and lanes

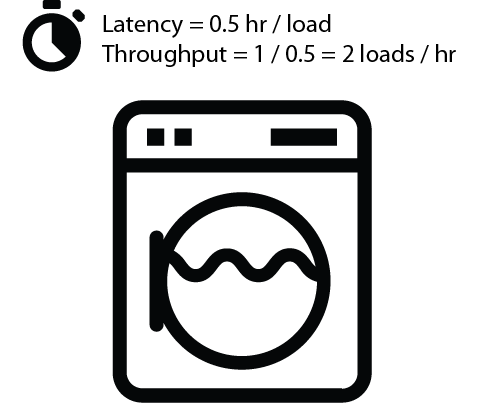

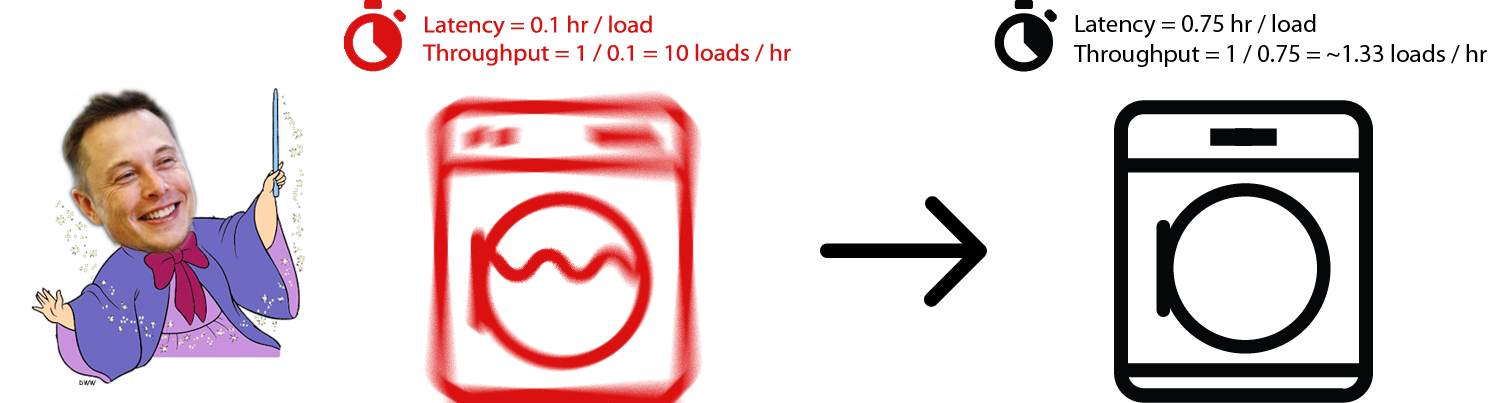

When describing systems of all kinds, engineers use the terms throughput and latency to formalize these concepts of effectiveness. Throughput is the total number of items of some kind a system can process — a transit network’s throughput is measured in passengers per hour. Latency is the time it takes for an individual item to be processed, or in our case for an individual to make a journey through a network. I first encountered these terms in a class about computer processor design, which used laundry machines to analogize the concepts. With a single laundry machine, the latency and throughput are simple inversions of each other; the faster the machine finishes a load, the more loads per hour you can run:

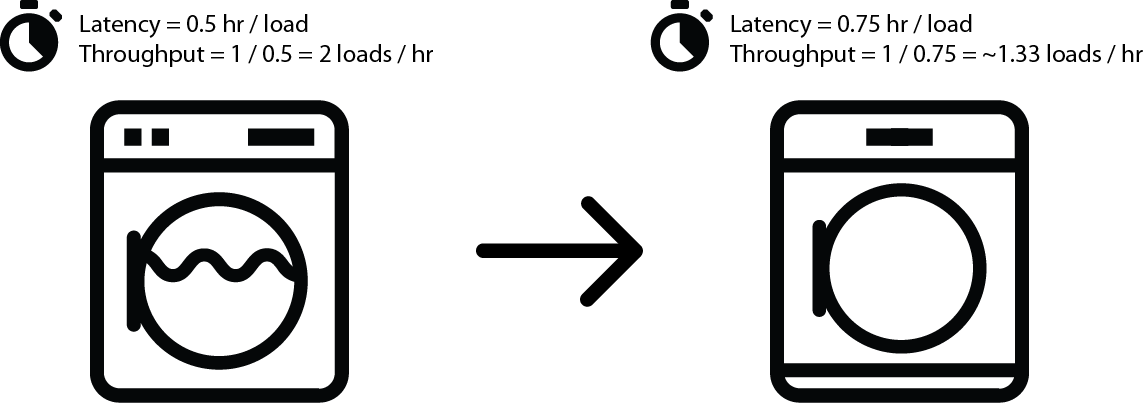

But laundry, like traffic, is a process that happens in sequential stages, going from the washer to the dryer before reaching its final destination, a pile on the floor:

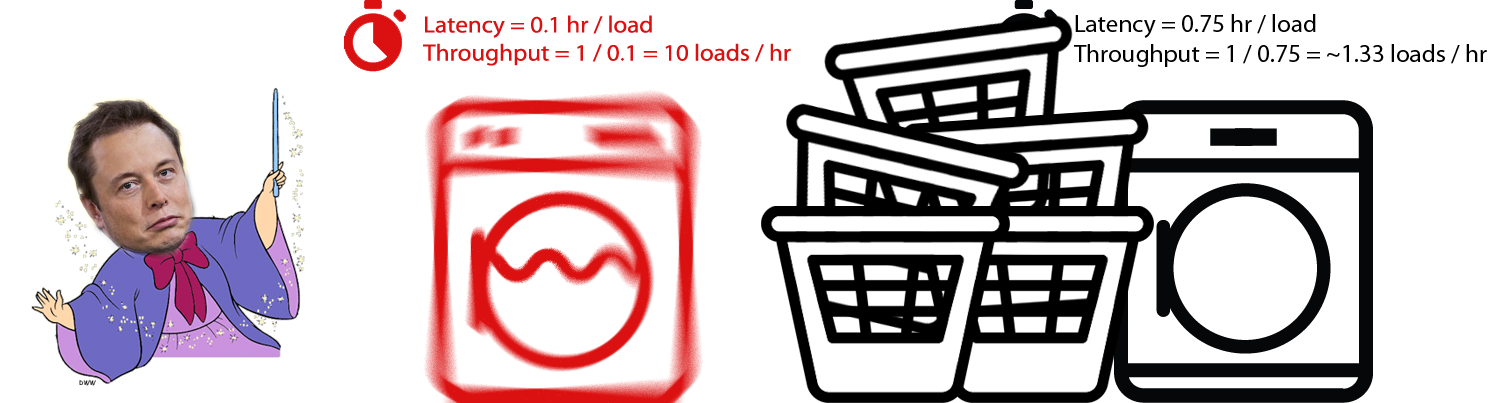

The latency of this kind of system is the sum of the latencies of each stage, and its throughput is the minimum of the throughputs of all the stages. So in the washer-dryer system above, we’ll never do better than about 1.33 loads per hour, and the mismatch between the two machines’ latencies is reflected in a queue of increasingly wrinkled laundry waiting to enter the dryer. Now let’s consider the effect of an Arrivo-style proposal to decrease the latency of a single stage:

Since we’ve clobbered the latency of this stage, we’ve drastically reduced the latency of the entire system, right? Well, no. In the rush to get away from traffic we’ve utterly forgotten why it exists in the first place. We don’t have highway congestion because the latency of a highway is large; it’s because the throughput of the city streets that the highway leads to is capped, leading to a situation more like this:

No matter how fast we can make these vehicles go and how closely they can follow one another, they can’t exit the Arrivo system any more quickly than the urban street grid can accept them, making this system as functionally useful as an extra freeway lane at rush hour (of the kind that increased peak travel latencies in LA). Bounded by the throughput of urban streets running at capacity during rush hour, the Arrivo network will be a very fast trip into a very long queue to get onto the street: the epitome of “showing up early just to wait in line”.

The throughput of single-occupancy vehicles in a city quickly brushes up against constraints fundamental to the very purpose of urban planning, which is to create desirable places for people to live their lives. We can’t increase the speed at which vehicles travel through the city without making it unsafe for pedestrians. We can’t widen roads or build more parking without cutting into space for activites that are valuable in both economic and human terms. These aren’t hypotheticals — we tried doing all of these things in the age of the interstate, rended the fabric of our cities, and are now spending billions upon billions of dollars to re-apply urban planning principles we had figured out before WWII. With a model that relies on increased throughput of cars through urban spaces, Arrivo endeavours to build a system that grafts technology that is so 21st century that it doesn’t even exist yet onto the very worst of 20th century urban planning.

The part where I tell you trains are cool

In America, we struggle to effectively finance transportation projects built from proven and cost-effective technologies, to say nothing of autonomous maglev pods. Imagining for a second that there was money floating (heh) around to build such a system, the immediately obvious thing to do is close it off from city streets and run high-capacity vehicles, called trains in industry jargon, instead of car-pods. Why?

By isolating the right-of-way from street traffic entirely, it becomes much easier to reason about the expected throughput of the system, because vehicles don’t have to merge — they just run back and forth2.

Until the system exceeds “crush load” capacity where passengers are struggling to board the vehicles, the vehicle throughput has little relation to passenger throughput, which is what we ultimately care about.

This isn’t just a question of access and equity – it’s a business concern, too. If you’re operating a maglev network and faced with the choice of running car-pods or trains, the number you’re going to be concerned about is the farebox recovery ratio, which describes the percentage of operating costs that are covered by user fees:

There is no part of this equation that favors car-pods. Farebox recovery is a numbers game — the more riders the system supports, the less you have to charge each of them for each ride, and roughly speaking, a subway can deposit about an order of maginitude more people into a city at rush hour than a highway lane. The marginal cost of each car-pod rider is huge compared to a train as well. Electricity isn’t free, and cars weigh 30-40x what their occupants do and will be proportionally more expensive to transport. Then there’s the fixed operating cost of maintaining a fleet of many more car-pods than will saturate the network so that they can roam the streets looking for passengers. With a tiny capacity compared to a metro and much higher operating and marginal costs, riders would be looking at paying 10-30x the cost of a subway ride to match the farebox recovery ratios of American subway lines – for instance, Boston’s Red Line operates at or over capacity every rush hour and still operates at a loss with an FRR of 60%3.

I could be wrong! I often am! Demand for such a service could soar, allowing the operator to charge truly exorbitant rates and make a profit on operations. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a few thousand people who would pay $200 to shave a few minutes off of their commute through Manhattan every rush hour, but I doubt there are many who take Colorado’s E-470 toll road ringing Denver, where the initial Arrivo segment is proposed. Moreover, I can’t emphasize enough that none of this has anything to do with the unknowably high capital cost of actually constructing such a network, which must either be offset by further increases in fares or justified as a public expenditure, as we do for proposals that represent a public good. Arrivo will bear neither. No government should commit funding for it, and no investor in their right mind would expect a return on its construction.

As much as I have written a few thousand words ragging on Arrivo, I would really like the Silicon Valley set to make a serious contribution to the problems of urban transit. But where the Boring Company is at least trying to lower tunneling costs, which is a win for effective mass transit as well as whatever Elon has verbal government approval to build today, Arrivo offers nothing to advance the conversation about urban congestion. The technology they’re chasing may have enormous value and I wish them all the best in developing it, but it would hardly be worse at “ending traffic” if their proposed maglev lanes featured a Hot Wheels loop-de-loop in the middle. We don’t need a bunch of guys in a kitschy LA garage-office to tell us that shooting large vehicles on top of larger vehicles down a magnetic track is cool as hell, but won’t solve urban congestion. There’s a Silicon Valley truism that “those who say it can’t be done should get out of the way of those who are doing it”4. My blog that no one reads will not get in Arrivo’s way, but I hope they take a moment to think about, and perhaps reframe in light of well-known constraints, what it is they are actually doing.

Image sources: fairy godmother, Loka Mariella’s laundry icons, and Gregor Cresnar’s timer icon. Thanks!

- Hate the name if you want but the story of how he got it is kind of adorable. [return]

- This is a simplification even for simple branching transit systems and a pleasant fantasy for a system like New York’s, but even the most complicated subway system is a tractable network to analyze compared to even a modest urban street network. [return]

- It’s true that a fixed operating cost absent from the car-pod model compared to Boston’s is the salary of train operators. But any high-capacity train on Arrivo’s maglev would be fully automated. [return]

- It seems that those who say it shouldn’t be done are often asked kindly to get out of the way as well. [return]