Fare Hikes and Feedback Loops

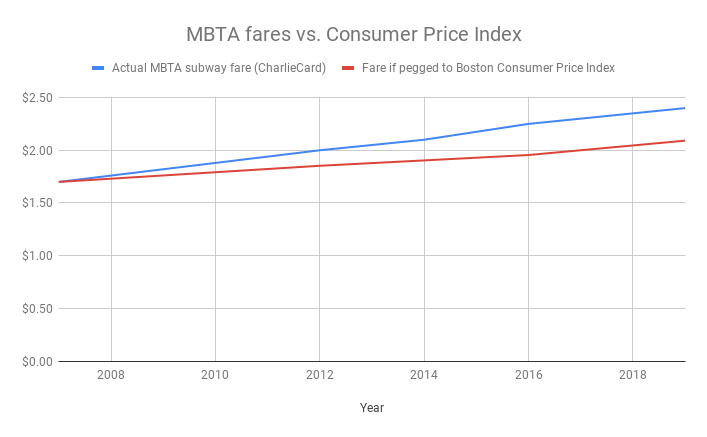

My friend Kenny messaged me the other day asking for a quick take on the proposed 2019 MBTA fare increase of 6.3% – in brief, it would raise the cost of a subway ride from $2.25 to $2.40. That spiraled out of control into the draft of a Twitter thread, which made me remember that I actually run a blog about transit and haven’t posted for a while, so here we are.

That the MBTA needs to raise its fares from time to time is inevitable. Fares account for about 30% of the agency’s revenue, and their day-to-day operations rely on that stream of cash keeping up with inflation. As the T calmly explains on its website:

While the MBTA continues to focus on controlling costs and growing non-fare revenue, this proposed increase, which is in line with the rate of inflation in the Boston area, is necessary for the Authority to continue making system investments to improve service.

It’s certainly true on the surface, but there a few things that are misleading about this statement. The first is that, as far as I can tell, the cost of a ride on an MBTA subway has not had any trouble keeping pace with inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index). Here’s the data starting in 2007, when the CharlieCard and its fare structure were introduced:

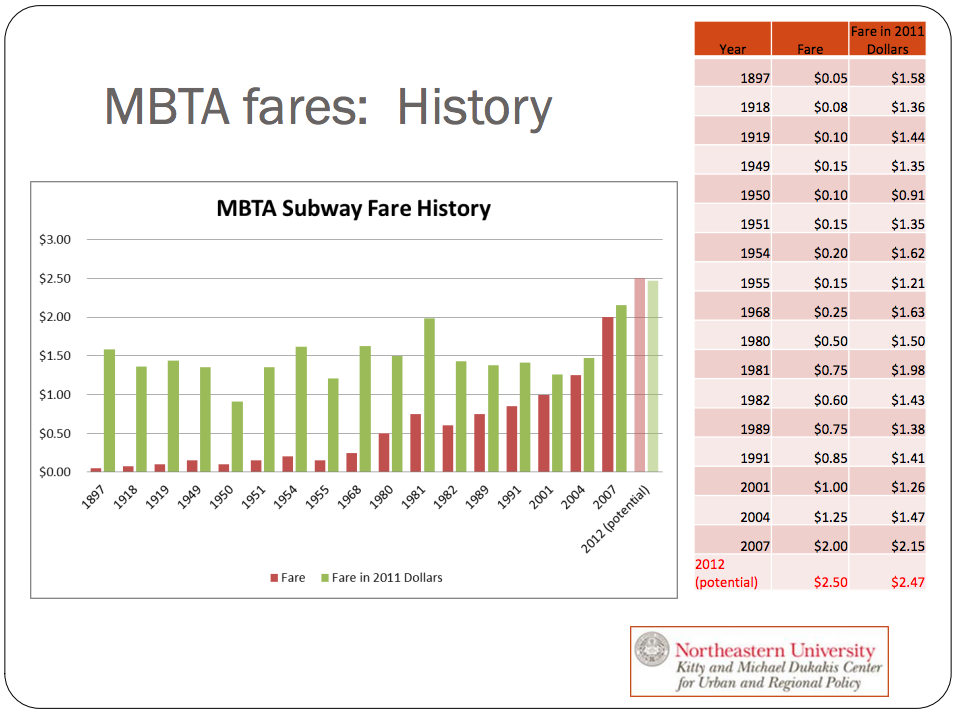

The second is that while MBTA fares have increased more or less monotonically thoughout the ages, they haven’t tracked inflation very closely at all, and in real terms they’ve varied quite widely:

A reasonable objection here would be that transporation operating costs don’t necessarily track with the consumer price index, which is fair – most consumers aren’t running trains or incessantly repairing escalators. The MBTA can look at their budget, identify a revenue shortfall, and close the gap by passing the cost along to their riders. But doing so at this moment in time is shortsighted when you take a broader view of the agency’s purpose, goals, and importance to the region it serves.

The point of MBTA isn’t to make money – it’s to move as many people as possible “swiftly” and efficiently, and to guarantee a baseline level of mobility independent of income or ability. Regions with really good public transit have a lower proportion of automobile trips, which is good for the environment, too. Since its services take about 660,000 people on a round trip each day (that’s about the population of Boston!) the MBTA plays an important role in shaping the outcomes of social and environmental policy for the state of Massachusetts. Well, we’re at a moment in history where we could really use some good social and environmental policy. The United States needs to fundamentally rethink the way it lives and commutes to minimize the chances of us all falling into the drink sometime in the next century. We’re also in the midst of a national conversation about well-funded transportation can have transformative impacts on our health and social mobility.

Why (not) raise the fares?

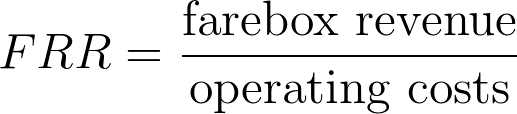

So, we need well-funded public transportation, so let’s fund it, right? Well, it might not be that simple. Consider that the efficiency of a transit service is often judged by its farebox recovery ratio (FRR), its revenue divided by its operating costs1. The MBTA’s argument for raising fares is essentially that it wants to keep its FRR constant by raising the numerator of this fraction. But they’re also betting that this increase won’t further tank ridership.

They’re probably mostly right – lots of people depend on the T, and sadly those who depend on it the most will be hit the hardest by this price hike. Still, because of the increase, a few more groups of college students will run the numbers and decide to split a Lyft. A few more people will just decide to drive to work, further choking up Route 1 and driving up the state’s yearly roadwork bill by a few cents each day. A few more people might just stay home. None of these things are catastrophes, but they shift the calculus ever so slightly, and the next time Charlie Baker’s office looks at the FRR, someone will start to wonder what they can do about the denominator.

High ridership means leglislators pat themselves on the back and clear a path to future service improvements, which means higher ridership in the future. Low ridership means a struggle to justify existing service – cue murmurings about Uber and Lyft2 – which could lead to cuts things like weekend commuter rail trains or hard-won night bus service, unsurprisingly dragging ridership down further. Cheap gas has made driving more appealing and driven recent declines in transit ridership in almost every American city. The two exceptions are Seattle and Houston – both cities that have made leaps and bounds in improving the quality of their bus networks over the past five years or so. Seattle has been installing bus lanes and queue jumps like nobody’s business, and Houston basically redesigned its bus network from the ground up to maximize the usefulness of its routes.

In neither of these cities did these things just happen – it took acknowledgement from regional leaders that they control a key part of the service-ridership feedback loop.

You find us the money, if you’re so goddamn smart

Okay, let’s get pragmatic for a second. The MBTA had a $70 million budget shortfall in 2018. If I’m lucky, someone from the T is reading this in a thirteenth-floor office, draft budgets strewn across their dimly-lit desk, the sun long set. They clutch their coffee mug so hard it might break and wonder “where does this punk think this money’s gonna come from?”. I’ll spare you a detailed description of my preferred plan – luring Jeff Bezos into the Seaport with tax incentives and literally shaking him upside down – and focus on practical solutions.

Working with MassDOT and individual cities and towns, the MBTA can improve service and drive revenue by dual-wielding a carrot and a stick. The stick is congestion pricing3 – charging people to drive their cars into busy areas at peak times. This sucks for people who have to be in busy areas at peak times, and and will make them mad unless you offer them a carrot, which is massively improved bus service. The T already knows that the secret to this is bus lanes, and mostly just needs money to paint them and do traffic enforcement around them. Tie these two concepts up with a neat logical bow – you can either pay the true cost of driving your car into downtown, or you can just get on a bus and sail past all those schmoes paying the true cost to drive their car into downtown – and you’ve got more enthusiasm for taking the bus, a higher farebox recovery ratio, and more revenue, with much less pressure to increase fares.

So, yeah, the price of a bus or subway ride is probably going to go up this year, despite all of this complaining, and it’s not the end of the world. That said, Governor Baker has committed to restricting fare increases to 7% every two years. In two years (more commonly known as one half-election cycle) we could be going through this whole rigmarole again. Or Baker could commit this year to raising that next 7% through congestion pricing and improved ridership. We’d put a few more dollars (in real terms) back in the pockets of people who need them, a few fewer pounds of CO2 into the air, and heck, I think we’d just be happier about the whole thing.

- The MBTA’s FRR is about 30%, though if you just look at the subway system it’s closer to 60% and quite high compared to its peer systems. [return]

- Mostly anyone who cared to click on this knows this anyway, but both of these companies posted huge losses in 2018 and their business model is insulated from the market by venture capital!!1 Relying on them to solve our urban mobility problems is a recipe for disaster. [return]

- This is, bafflingly, also called decongestion pricing by advocates who want to put a more positive sounding name on the concept. If you ever see that term just know it’s the same thing. [return]